“In the early days, people trying to escape from North Korea were executed in public if they were caught. Going to China was seen as a conspiracy against the government. That hasn’t changed. Escape is still seen as treason, a crime against the country,” North Korean defector Eun-Ju Kim told Tim Franco. For the past three years, the Franco-Polish photographer, member of the Inland structure, has been working on Unperson, a book project dedicated to these individuals who risked everything to start a new life, far from the dictatorship. A work mixing photographic experiments with poignant testimonies.

Fisheye: How did you turn to photography?

Tim Franco: As a teenager, I loved music. In 2000, I created an online music magazine. It was the beginning of the internet. I got invited to many concerts, which I documented. I remember that at the time I was using disposable cameras – which may sound a bit ridiculous, but it got the job done!

Seven years later, in Shanghai, after working in different industries, I used a camera – digital this time – and naturally I started taking concert photos of the Chinese underground scene again. I found it exciting. At the same time, I made my first pictures for Le Monde. China, at the time, was a country which attracted a lot of attention. Everything happened very quickly and I became a full-time photographer.

Documentary photographer, photojournalist… What kind of photographer are you?

For many years, I wanted to define myself as a photojournalist. That’s how I started. At the time, the big names of the press made me dream, but I realised that I preferred to take my time. So, I invested in an old 4×5 camera and started capturing the city of Shanghai as it was undergoing a rapid transformation. Working with a view camera, taking the time to compose each photo was very appealing to me. I would say that I spend a lot of time thinking, researching, before arriving at the final moment of capturing the image.

How did you come to be interested in North Korea?

After living in China for about ten years, I moved to South Korea. I had just published Metamorpolis, my first major project on the city of Chongqing and I needed time before I could get back into a new project. At that time, I was gradually discovering South Korea, but North Korea was still a mystery to me, even though the border was barely an hour away from my apartment by car. I didn’t necessarily want to go there at first, for fear of taking the same pictures you see over and over again, yet, I still wanted to learn more.

What did you focus on?

I became interested in defectors (people leaving their country to find refuge in another – often adverse – territory, ed.) living in Seoul. I then realised that they were really the only real witnesses in this country. Not only were they born and lived there, but they also had the experience of a capitalist life. I found their points of view absolutely fascinating. What’s more, the stories of their defections are often adventures as incredible as Hollywood movies. So, I decided to take an interest in them first, to listen to their stories, to photograph their faces, to try to understand this mysterious territory that is North Korea. I ended up working for three years on this project.

The title of your book, Unperson, is a reference to 1984 by George Orwell. Why did you make this connection?

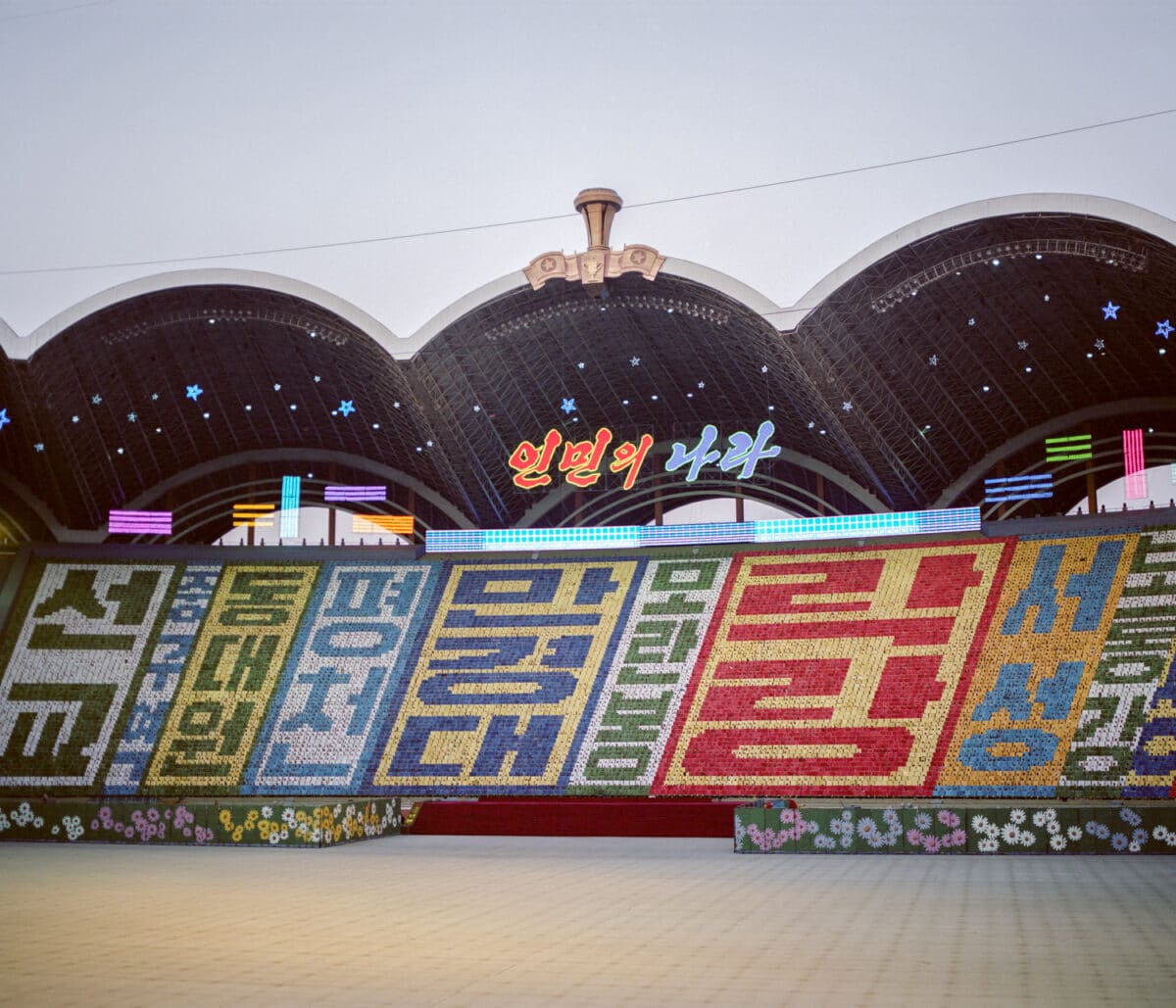

The ten days I spent in North Korea were among the strangest of my life. It really felt like entering a parallel world. My first impression? I discovered a very beautiful, clean country, with handmade propaganda paintings, monuments of disproportionate size… But quickly, anxiety caught up with me. I absolutely could not mention my book project, in most situations. We had to be careful how we stood, not pointing fingers or crossing our arms in front of representations of leaders, etc…

After these ten days, I was mentally exhausted. I was traveling with a journalist friend with whom I shared hotel rooms, and we were constantly careful, especially inside those rooms, not to say anything, not to do anything that could offend the leaders. At the end of the stay, I found myself talking about Kim Jong Il and calling him “The dear leader” out of habit. The brainwashing had already taken place.

What struck you the most?

When I came back, I realised that I was having a hard time digesting the trip. I didn’t know if I had learned a lot or if, on the contrary, I hadn’t retained much. The vision given by the guides is very different from the one given by the defectors.

But I still had the impression that part of the population – of the capital, in particular – lived a more normal life than one might imagine. What struck me most was how North Koreans saw the Korean peninsula as one country, which was undergoing a momentary fracture. They are curious about the South, follow the meetings between Kim and Trump with attention and are full of hope for a future reunion. In South Korea, few people are interested in the North and the mere idea of unification feels like an impossible ideal.

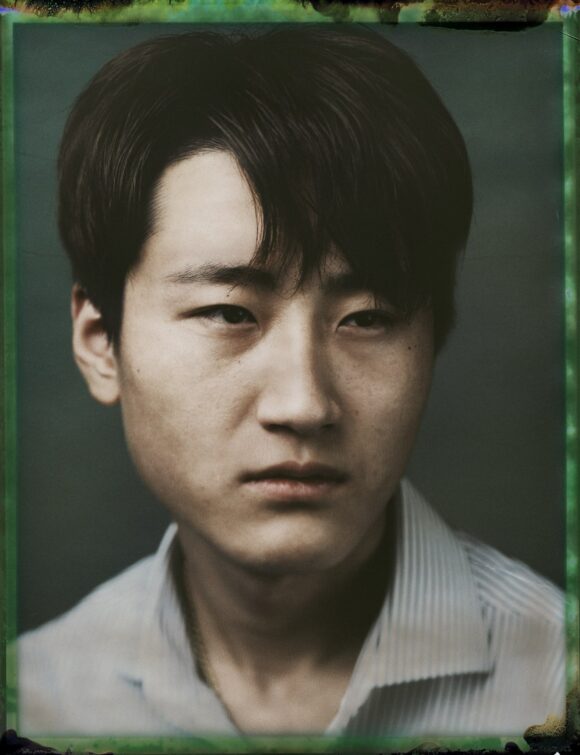

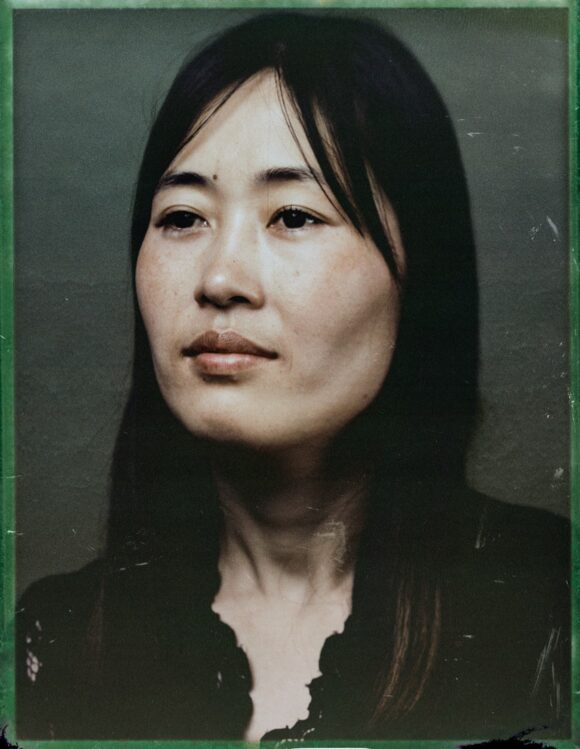

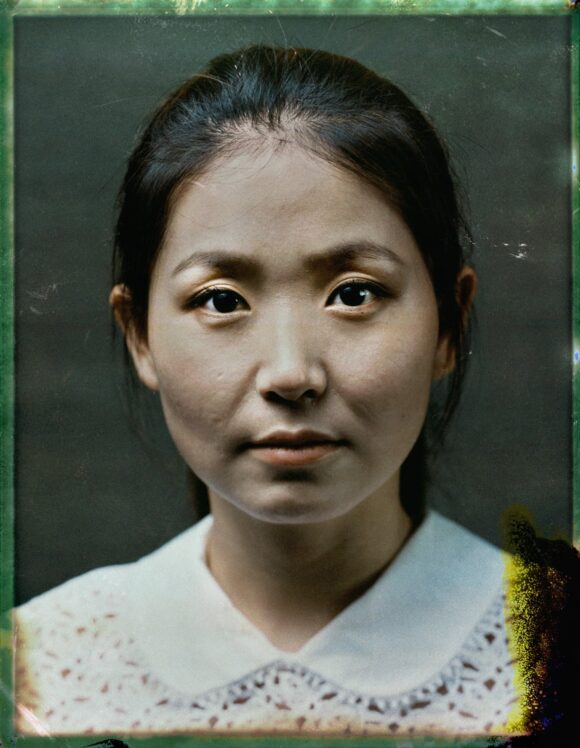

Who are the people represented in your photos?

They are the defectors. I decided to meet a rather eclectic selection of them. From North Koreans from the poorest regions, who have often fled out of desperation, to the more privileged North Koreans, coming from big cities like Pyongyang, who have decided to leave out of idealism.

The biggest problem with their testimonies is that it is impossible to verify their stories. That is why it is difficult to qualify this work as journalistic, for example. Some defectors have developed the habit of exaggerating their stories in response to public interest, as a result of being interviewed. I was also surprised to see how much the North Korean community lives in seclusion in Seoul. Not by choice, but often because they are often not completely accepted in this society. As a rule, the international community is more interested in them than the South Korean population, which lives with the still-present fear of an attack from the North.

How did they react to your project?

It is difficult to find North Korean defectors who agree to be photographed. Some of them don’t want to reveal where they live or work. So, I had to create a safe place to welcome them. I built a studio in the official press building in the center of Seoul. As the portraits could not really be documentary, I looked for a way to reflect the subject of defectors through a particular technique.

What is this technique?

Each portrait was made with the 4×5 view camera with instant polaroid film. This film gives a usable positive and a negative which is not, and is normally thrown away. I decided to use this negative by purifying it with chemicals. The idea was to use material that is not meant to be used to reflect the existence of these North Koreans in South Korea. Moreover, this chemical purification results in a series of imperfections, ranging from scratches to chemical spills. This result, often uncertain, reflects rather well the incredible adventures of these defectors, which can last from weeks to years.

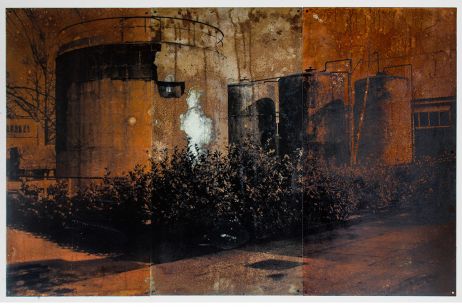

You mix portraits with landscapes in your book. Can you tell us more about these panoramas?

While listening to the many stories of the defectors, I discovered, little by little, all the different routes. In East Asia, only two countries recognise the status of North Korean refugees: Thailand and Mongolia. Since they cannot cross directly south – the DMZ, the demilitarised zone built in 1953 that separates the two Koreas, preventing them from doing so – the defectors must first go to China, where they are often persecuted and arrested. They must then either travel to Mongolia through the Gobi Desert or head south through China and then pass through Laos or Burma into Thailand. These journeys are long and dangerous, and North Koreans who are arrested along the way often find themselves in a political prison in their home country.

In much rarer cases, defections can occur at the DMZ or by boat. In most cases, the defectors crossed incredibly different landscapes, from the icy rivers separating them from China, to the Gobi Desert, from the big Chinese cities, to the canoes of the tropical Mekong in Thailand. So, I decided to retrace these paths, from North Korea to Seoul, to photograph them.

Why publish this project as a book?

It is important, in my opinion, to delve into the individual stories of each defector. I find that the book allows readers to immerse themselves in these stories while observing the faces and landscapes. The objective was also to deal with North Korea on a more human scale, but the problem remains complex, and the book gives time to absorb each story at its own pace.

You can pre-order the book Unperson through the crowdfunding campaign (104 pages, from €32).

© Tim Franco