Photographer Lynda Laird grew up on the wild and windy Orkney Islands, in Scotland. Her main source of inspiration is the sea, and her main interest is the spatial dimension of memories. It is not surprising then that when she stumbled upon Deauville orphanage, in France, she could not look away. This forgotten place once housed the orphans of the fishermen lost at sea. We interviewed Lynda about the series she built there: L’ amour lui même doit s’endormir (Love itself shall slumber on).

Where are we Lynda?

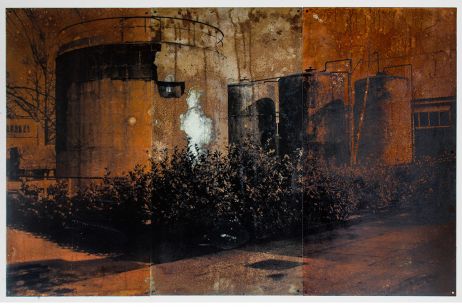

We are in a building that was created to house children who had lost their fathers to the Sea. This building has a long story. It first evolved into a shelter for any children in need of a home, ran by the Franciscan nuns. In the First World War part of it was converted into a hospital for soldiers, and during the Second World War it was evacuated.

Why did you adopt the constant pattern of capturing the windowsills?

I focused on the windows of the bedrooms because they felt the most poignant to me. They all had different curtains and it felt like even though the building was a sad place and full of loss, they were trying to bring some beauty and color into it. The windows represent a kind of hope, a different view and a gateway to somewhere else, somewhere the children could escape to.

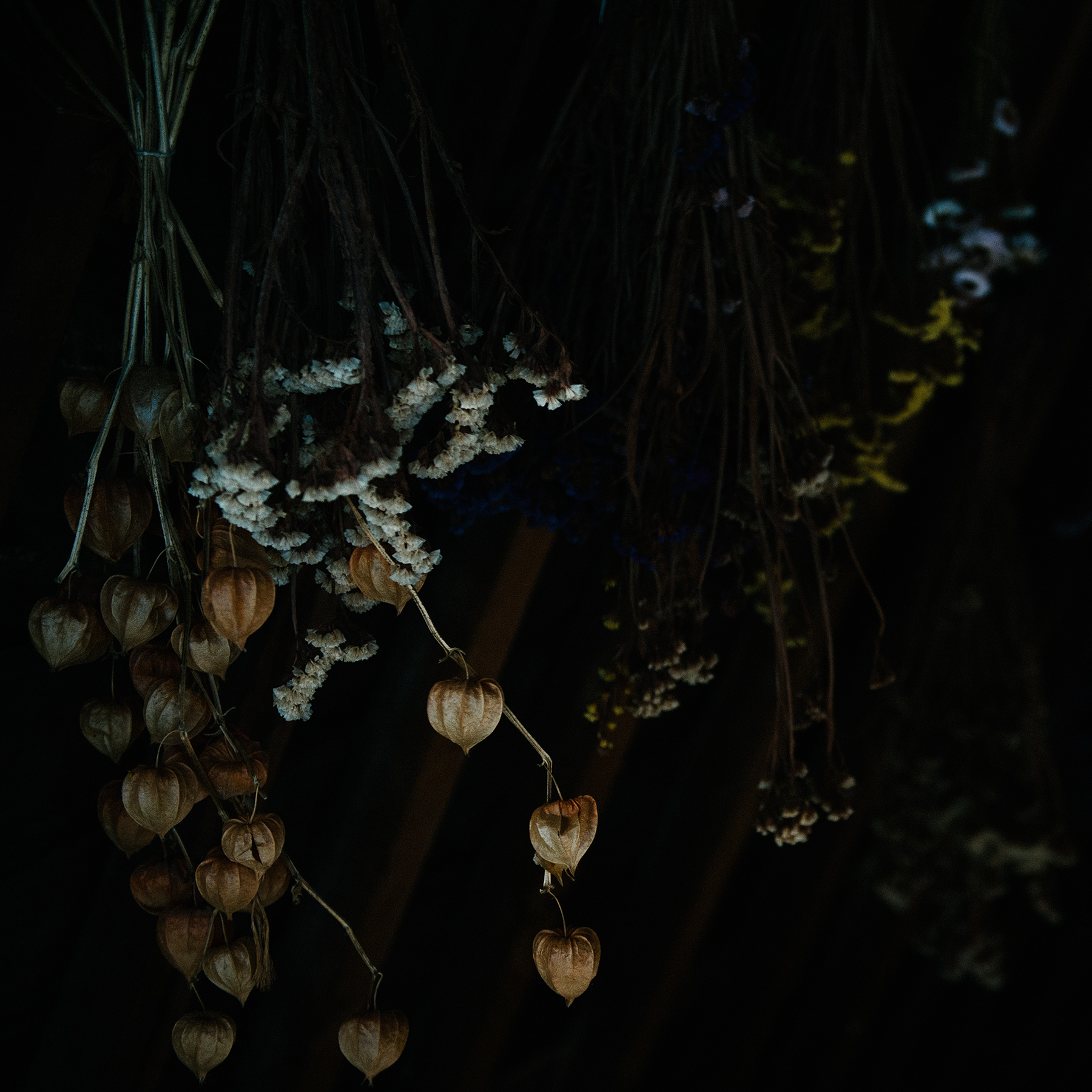

What is left in the building now?

Seagulls. To me they were important as their sound was very present no matter where I was throughout the building. The birds would sit on the roof looking in to the courtyard and they had dropped a selection of shells and seaweeds in to the building. In folklore seabirds are said to take on the souls of lost sailors and I really liked the idea that these birds were in a sense the fathers watching over the children, dropping in offerings from the sea as a way for them to remember.

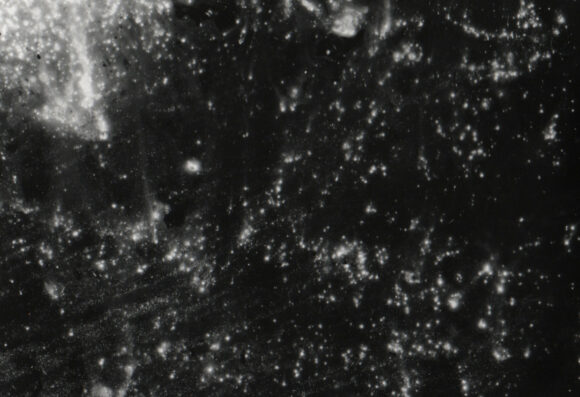

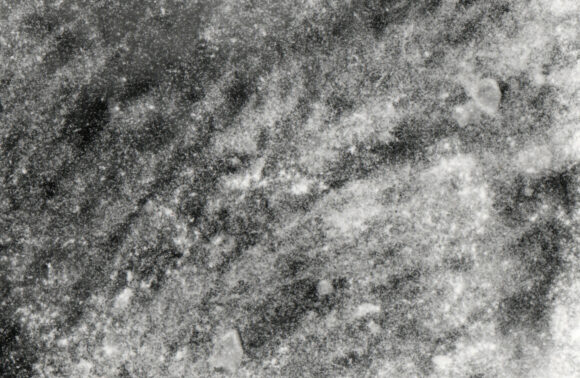

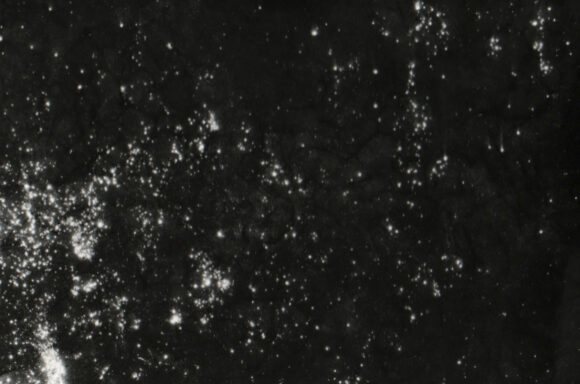

You exposed the orphanage images coupled with pictures of the sea, shot using water as a lens. Why?

I chose to make images in the sea using the water as a lens because I am interested in the idea that there is memory stored in water; I already built a body of work on this concept. Anything that has touched the water has left a trace in its substance. Although controversial, it’s a concept that came to light in the 80’s by a French immunologist called Jacques Benveniste who worked in the field of homeopathy. I really loved this idea and by making these prints, by placing photographic paper in to water and exposing it, the paper holds a trace of the sailors who lost their lives to the sea. I made a print for each bedroom that remained in the orphanage.

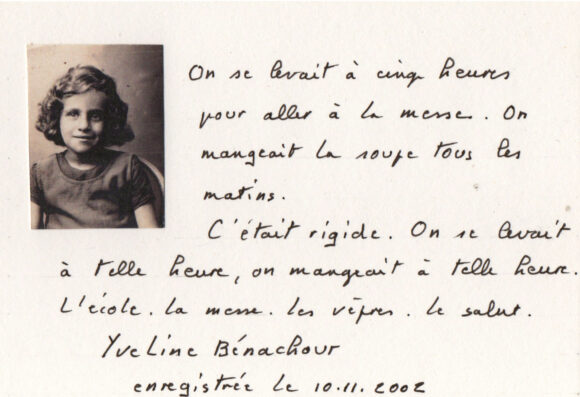

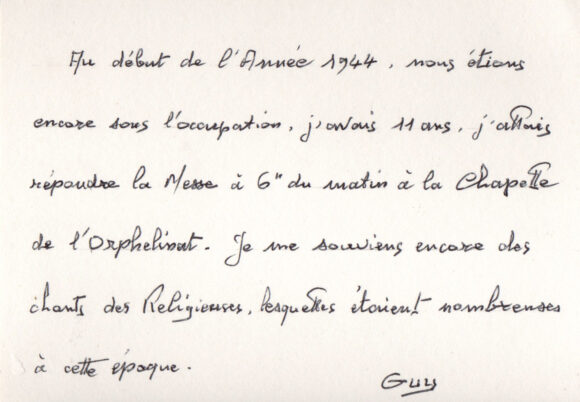

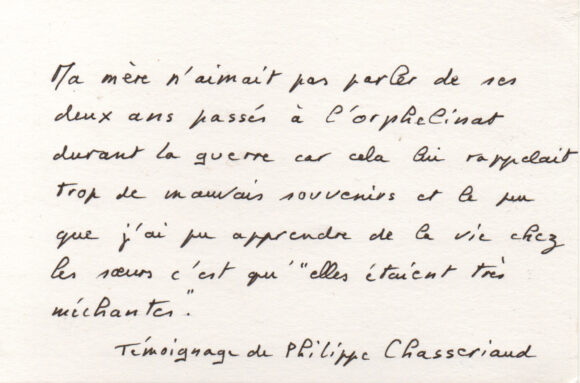

Why did you decide to include bits of the orphans’ letters in the series?

The immanency of memories in objects is invisible to the naked eye, and I am interested in showing it. I always work with video, sound and archive. Collecting objects and testimonies from these spaces as well as employing camera-less techniques in an attempt to find a way to collaborate with the subject. I like to work with the materiality of specific landscapes, bringing a trace of it’s history and memory into the work.

What is the relationship between memory and photography?

In an interview Susan Derges, an artist whose work I love, said that photography is linked to death in the sense that when viewing images you are looking at absent moments. I think that’s a big link between memory and photography. Photography makes us look back at moments that are frozen in the past, it can act as a trigger for stimulating memory. It can also change the way we remember things, by planting seeds in the mind that are different from the memories we have. We build and change our memories with the images we see and the people we talk to. In “Pieces of Light”, a wonderful book on the science of memory, I read that “memory is an artist as much as a scientist”.

Images from “L’amour lui-même doit s’endormir” © Lynda Laird