In December 2001, populous riots ravaged Buenos Aires. Citizens were protesting against their President’s neoliberal policies, in order to hold him accountable for the country’s poor economy. Under the brutal military repression, a group of photographers came together to capture these incidents that shook Argentina. 15 years later, we spoke to Sub Coop, that now is a leading Latin American Photographers’ cooperative. Sub Coop uses visual storytelling to illustrate social fervor, keeping collaboration at the heart of the organization.

Fisheye: Why do you call yourself a “cooperative”?

SubCoop

: During the riots that marked the genesis of SUB, there was a lot of political creativity and popular participation. The crisis of traditional hierarchical structures, and the popular assemblies in the streets inspired the configuration of SUB. We are structured like a workers’ cooperative. Photographers never put their own signature on the series they shoot; every piece of work is a collaborative product, signed by Sub. We even divide the profits equally and share the same revenue, no matter who sells more photographs. We always put the Sub project ahead of individual careers. We believe in collective authorship and together choose our subjects, their articulation and the aesthetics of every series. There is no hierarchy in SUB, and it doesn’t matter who is the one clicking the shutter. The collegial essence of SUB is grounded in its political background, tied to the historical moment in which the collective was born.

How can you collectively determine the aesthetics of a series?

In a collective, it is very important to define a common photographic language. Since everyone’s photography is naturally personal, in order to work collectively, it is paramount to designate a specific framework of photographing before the shoot begins. It all starts with technical decisions. For example, we discuss whether we should create more silent images to accompany a speech, or louder ones that speak themselves. We determine beforehand if we should use “reportage” techniques or more artistic ones; and if we are going to shoot portraits, we collectively establish the distance we should take from the subject.

How did your work change after the end of the riots?

In 2001, there was limited digital photography and we were responding to the urgent need of documenting the uprisings. Our collective stems from a necessity to intervene, to narrate the political turmoil in first person. As we democratized the means of production and diffusion of images, our primary need to “be there” was overshadowed by the care for deeper information and details. We realized that once we got rid of the necessity to communicate in cases of urgency, we could devote more energy to research. Since 2007 we have produced deeper work, sharper, and more pertinent. We developed the aesthetic means to enhance our point, and worked on our photographic formulations.

How do you manage to maintain your social intent while indulging in complex photography?

We’ve always drawn a parallel between documentary photography and literature. Rhetorical figures make stories more beautiful and more profound. In poetry, metaphors make the text more captivating. In refining our photographic language, we aimed at stressing our point, at expressing it in more perennial terms. For us, complex pictures are a weapon in the hands of an activist. However, we also realized that since Lewis Crane’s series on child laborers, photography has had a hard time changing people’s destiny. One day we presented “17 veces” (17 times), a work on an indigenous tribe, expelled 17 times from its land. During the exhibit, the tribe was expelled for the umpteenth time. Our reaction to observing this phenomenon was to start building different photographic narratives. Today our main target are the subjects themselves; we want them to use our pictures to establish their identity.

To what extent is your photography Latin American?

When western editors or curators look at Latin American photography, they seek the “3 Cs”: “Culo, Calor, Color” (ass, heath, color). As photographers, we often nurture this stereotype, by feeding the market with its demands. There are indeed typical features of Latin American photography, due to our climate and our lifestyle, but much of it is clichés and stigmatizations. Sub tries to diversify its themes and aesthetics, and to find alternative ways to represent our territory. While holding on to typical Latin American narratives, such as the mystical, magical allure that Garcia Marquez created, we try to represent the diversity of contexts and situations of this huge continent. In Buenos Aires, our photography is impacted by our soundtrack, – tango – and by the European heritage, that is very present; in Quito it can be a whole different story…

Why did you decide to shoot a series on the worshippers of “Gilda”?

Gilda was a cumbia singer who died in a car accident, venerated by a huge group of fans. For all the descendants of enslaved natives, syncretism is very important. In the past, catholicism kept them from professing their cult, so they dressed up their idols as catholic Saints. Gilda is venerated by people who do not find their place in society because they are gay, transsexuals, or eccentric artists.

What is the place of collectives in the world of photography today?

We participated in two Euro-American photography collectives meetings that took place in Sao Paulo and Madrid. During the meetings we realized that there is no precise formula to create a collective. Collectives are diverse in structure, goals and ideologies. I think that in general the concept of collective in photography is an efficient one, and society is slowly becoming aware of it. Collectives blossom everywhere and they are increasingly accepted by editors, journalists and curators. It is an intelligent move; if multiple brains think about the same theme, the result will naturally be better.

Can you briefly introduce your work “Huis clos”, about gated communities in Buenos Aires?

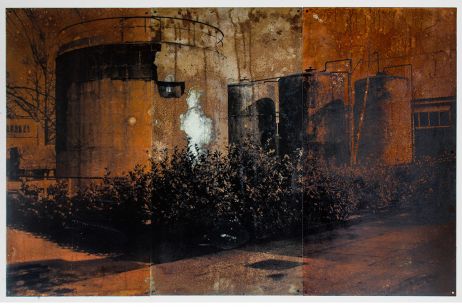

After a while we realized that Sub was copying itself. We were always tackling the same subjects, always from the same perspective. People who revolt, students, farmers… Pain is really photogenic. Rich people only appear in celebrity magazines, and they are portrayed as they like: they are rarely the subject of documentary work. It is also always riskier for a photographer to deal with people who have easier access to judicial services. In a slum, it is not hard to get nice shots – people think that their publication may improve their situation. Rich people do not want to be photographed -they have nothing to improve, no social complaint to throw a spotlight on. This time, instead of showing the poor, we captured gated communities, to display how people who exploit poverty live. However, in the process, we were careful not to hold any judgement on these people, and to approach the subject free of any ideological bias.

Images © Sub Coop