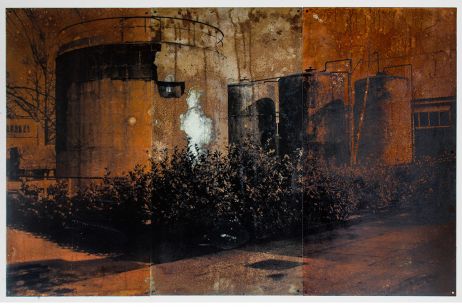

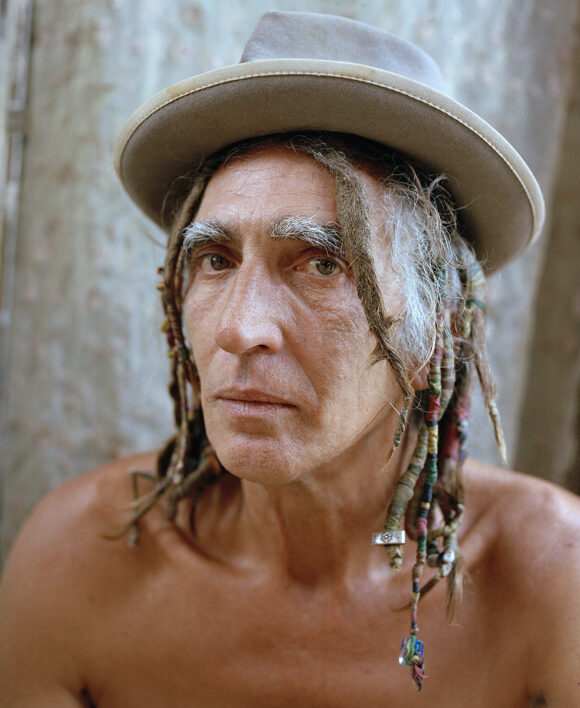

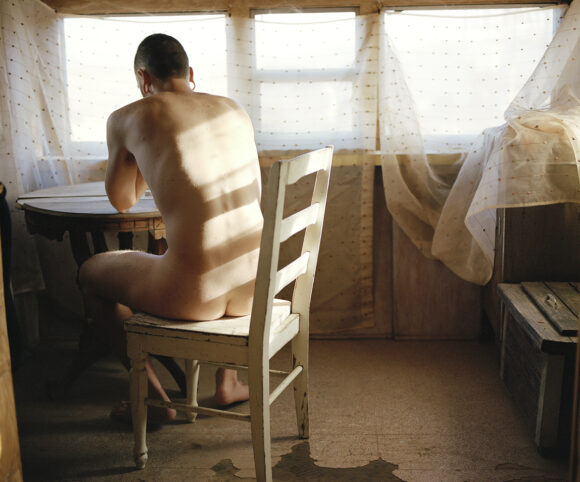

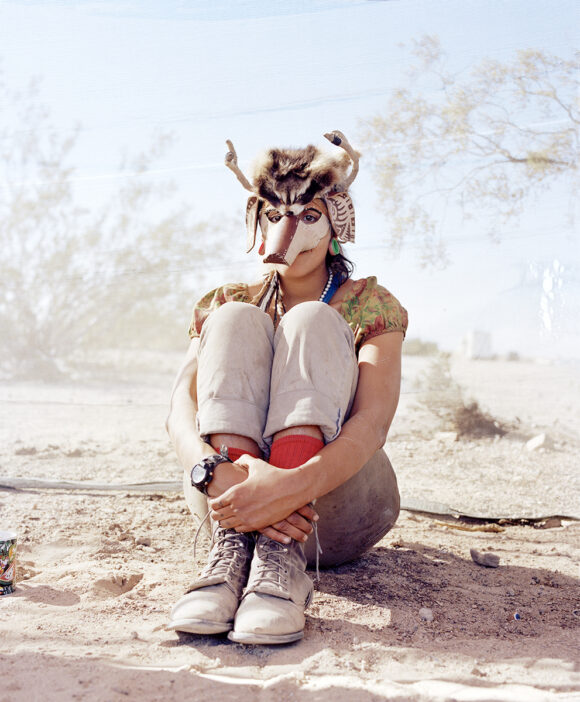

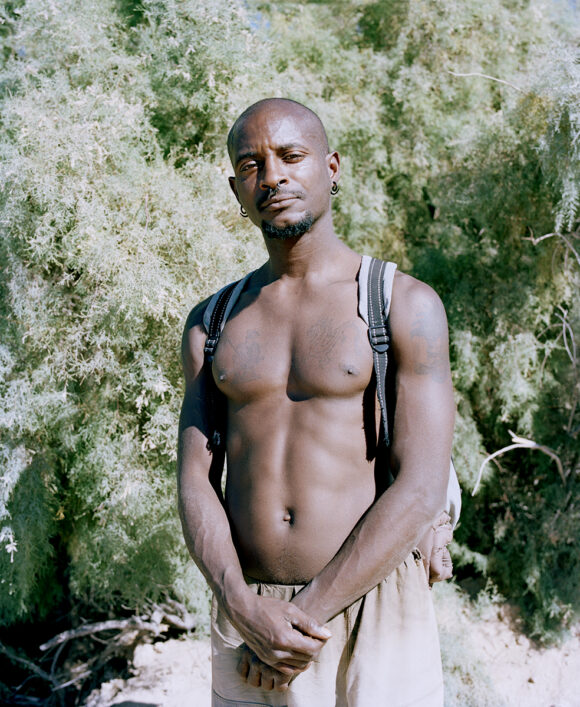

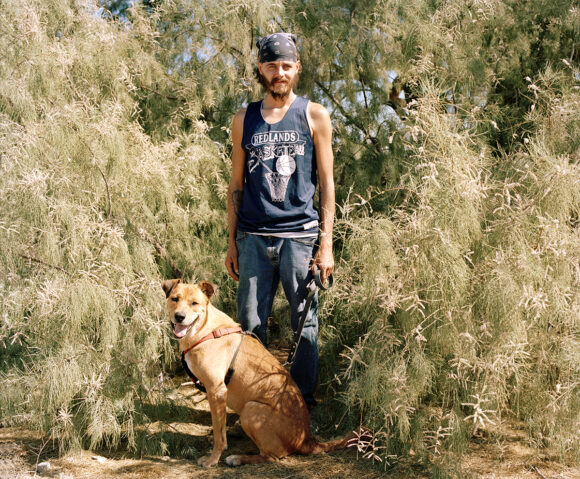

The last free place in America is a camp in the Californian desert, commonly known as Slab City. Here, runaway boys and old hippies live off the grid, in tents or caravans. In the Slabs there is no water, no electricity, no rules and a general consensus to live and let live. Built for military purposes in the 1940s, the camp was soon abandoned by the Marines. Twenty years after they’d first arrived, a new migration began, and now 150 people live there permanently, enduring temperatures that reach 50°C in summer. American photographer Rhombie Sandoval, 26, named her series after an inhabitable art installation in the area, East Jesus. Her beautiful portraits reflect the warm interactions she had with the community and her quest for herself in the Slabbers’ gazes. We spoke with her about this very personal project, “East of Jesus”.

Fisheye: Rhombie, how did you start working on this project?

Rhombie Sandoval

: While I was photographing people via Craigslist for an older project, I came across an ad by a guy called Dan, who was looking for a ride to Slab City. I decided to answer the ad, and a few hours later I picked him up and drove toward the Slabs. Dan offered me a place to stay at East Jesus, and when we arrived there I met Danielle and her husband, Zak. Danielle had recently beaten cancer and told me that she was happy that her hair had grown back. That night an altercation broke out in the camp, and Danielle escorted one of the women involved out of East Jesus. I followed them, and when the woman began pulling Danielle’s hair, I ran over and grabbed the woman’s wrist and carefully removed her fingers out of the hair. The following morning I asked to make a portrait of Danielle and Zak, and she allowed me to, because I had helped her. That was the only portrait I made that weekend, but when I developed the film and saw it, I drove back to the Slabs.

How did your time in Slab City impact you on a personal level?

My series “East of Jesus” would not exist if I hadn’t become part of the local community. I created a sort of family in Slab City. This integration gave as much to me as to the photographic project; making the transition from tourist to local is my favorite way of working. The time I spent there ignited me with a passion for listening to the others. It introduced me to those who walk on the wild side, and it instilled in me a desire to feel alive rather than just to be alive. East of Jesus is a collection of encounters that go much deeper than the photographs, and each helped shape who I am.

How are the Slabbers?

I will answer this question with a small text I wrote during a Thanksgiving spent in the Slabs:

“I am thankful for the drifters, dreamers and overachievers. The forever youngs and old-souled ones. The on-your-feet fearless fleet, those who don’t wait or procrastinate. The go-getters who don’t fear time, but chase their dreams to stay alive. The confused who feel lost but keep on trekking just because they are so close to that one something. The ones who live a life of their own, finding anywhere they go a place to call home. The strangers who are stranger than strange, they’ll always have a smile on their face. We don’t worry about class or race, that’s why I’m grateful for this place”.

What makes this place unique?

The local community in the Slabs is almost judgment free. The Slabs challenges the normative character society attaches to the pursuit of happiness. In Slab City they acknowledge that happiness varies from person to person, and that it cannot be achieved through a pre-set range of choices and actions. This community lives according to the principle that you can take whatever path you need to fulfill your dreams.

Why is portraiture your preferred photographic genre?

My first and primordial interest is listening to other people’s stories. People-watching is one of my favorite pastimes, and I spend hours observing the way people move and occupy space. Portraiture allows me to access that space. It allows me to ask the questions that my eyes constantly formulate. I may not always agree with what my subjects say, but I can often empathize with the emotions their stories emanate. I believe that by hearing another person’s story you become in a way responsible for it, and you owe it respect. I recently started an Instagram account—@AnywhereBlvd—where I share the stories behind other photographers’ portraits. I believe in the value of listening to strangers, to get closer to them and discover that you could have more in common than you think.

What do you think the photographic medium can bring to your interaction with someone you don’t know?

I am a relatively shy person, so my camera helps me interact with someone I don’t know. I often carry my Mamiya when I walk around. My camera sometimes starts the interaction itself, when strangers comment on it. When I set up to take a portrait, the photographic medium creates a space where my subject feels acknowledged. The action of making a portrait brings about an attention, as it is one of the few times where it seems acceptable to stare. The photographic medium creates a space to appreciate someone.

What is photography to you?

Photography is an opportunity to see yourself in another’s story. It is a tool with the power to illustrate the way we connect in this experience of life. Photography is a gift that provides an opportunity to listen and learn from anyone in front of your lens. It is a way to have your life impacted by the connection formed before, during and after you create that portrait. Photography is my way of growing as a person because you are given a responsibility to share the beauty you see in another. Photography is a question with an open-ended answer, it ignites your audience’s mind to form their connection to your subject. It is my favorite form of movement, but most importantly, it is an opportunity to learn.

Why do you prefer film to digital photography?

Since my camera becomes an extension of myself, the slow rhythm of analog photography has an impact on my own pace; it allows me to slow down. So many things in my life feel like they need to be completed quickly. There is always a pressure for instant gratification, but I appreciate opportunities for a slower pace of life. I don’t believe in rushing something I love. Shooting film includes a lot of waiting, but it helps me be patient. I spend more time thinking about what each frame will look like. I analyze my scans and really study where I can make improvements. I learn the most about myself when I shoot film. Also, there is something quite beautiful about the sound of film advancing. I love the feeling of satisfaction of holding a roll of film you’ve shot, and the excitement of taking it in for processing.

Images from “East of Jesus” © Rhombie Sandoval