Fisheye : How is your story different from all the others we have seen on Duterte’s war on drugs?

Lawrence Sumulong

: I returned to the Philippines during a halt in the drug war. I didn’t shoot at night nor did I cover live crime scenes. Instead, I came in with a specific visual idea exploring the aftermath of the drug war, knowing that this would be a portion in some broader body of work based in Manila.

I was namely reacting to the increased media coverage coming out of the Philippines. According to scholar Nerissa Balce, during the Philippine–American War, white supremacy and an imperial agenda were reinforced through the Western media’s dissemination of images of dead male Filipino bodies as well as pliant, scantily clad Filipino women. I was reminded of that historical moment with the sudden windfall of graphic imagery coming from the Philippines in the months prior to my visit. I wondered what it meant to be continually photographing and disseminating images of dead Filipino bodies for the consumption of an international audience. I tried to make that awareness, that frame of mind visible, while also expressing the raw emotions of the story that I was covering.

“In some sense, I did everything incorrectly – arrived late, missed moments, avoided the spectacular.”

How much did the fact of being “a local” impact your work? And the fact of being “a foreigner”?

I’ve tried to reconcile those two perspectives in every story that I’ve shot in the Philippines. The varying aesthetics in all my series reflects that and shows a type of discomfort with myself that I’ve cultivated. I am superficially able to blend into a crowd and have an innate familiarity with the culture and the city of Manila as a Filipino-American. However, I live in New York City and don’t speak Tagalog, which is profoundly alienating despite my love of the country. I wish to learn the language, but have yet to. It’s an awkward, in-between position that I’ve lingered in. I’m always trying to shoot from that liminal and unrequited state of being to show the reality of trying to empathize with what’s occurring in the frame while also recognizing the absurdity of that enterprise.

You said that through your work you question “the efficacy of still imagery and the veracity of the social documentary genre”. How so?

I found my visual concept and use of the forensic/full-spectrum camera to be secondary to the letters written by the victims of the drug war. Later, my collaboration with Manila-based street artist Doktor Karayom also proved to be more valuable than the notion of being the auteur or single author of this story. I’m interested in creating work now that’s layered, polyphonic and many-voiced, or in some sense interdisciplinary.

Can you elaborate a bit on the technique you used for the series and the reasons why you chose it?

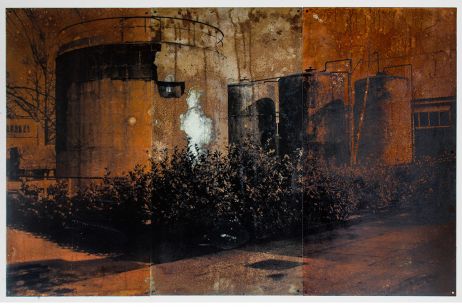

Given the subject matter, I wanted to use a camera that might be used for crime scenes and make a gesture to the practice of forensic photography. However, it didn’t make sense to be beholden to the compositional templates of medical imagery. I ended up using a “full spectrum” Nikon D5100 which captures a combination of infrared, ultraviolet and visible light. The majority of the photos were shot with a tilt-shift lens on that body to give a sense of instability and distortion.

On top of that, I used Lifepixel’s Super Blue Filter, which is very unusual and has no equivalent in the Wratten gelatin filter line. Its 50% IR pass frequency is 705nm, but in addition it also passes UV and blue light with a second pass band of 285nm to 465nm at 50%. I continually return to the poem “Separation” by W.S. Merwin, which expresses the overarching feeling and approach to color.“Your absence has gone through me Like thread through a needle. Everything I do is stitched with its color.”

The effect is very dramatic, your pictures are almost two-toned, blue and yellow. What is the meaning of these two colors in your series?

In the genre of Gothic literature, there is the presence of the sublime or the uncanny, which “derives its terror not from something externally alien or unknown but—on the contrary—from something strangely familiar which defeats our efforts to separate ourselves from it”. The use of a duotone helped to present this atmosphere of otherworldliness. It shows a type of netherworld that the bereaved and the society currently live in, where the drug war has mutated into a conflict where neighbors are seemingly exacting grudge killings and human connection has fully broken down into two shades.

The color yellow specifically holds a deep significance in Filipino history. On 31 August, 1986, two million people protested against martial law and lined the streets of Metro Manila. Yellow appeared as a symbol of unity and defiance. It will always be a reminder of those who sacrificed their lives during the Marcos martial law regime. I am using this color in a similar fashion, but in a new and equally terrifying context. Taken out of the Filipino context, the presence of yellow Asian bodies in the Western imagination perhaps recalls the racist ideology of the Yellow Peril. It is meant to announce a knowingness that these images are being disseminated and consumed by the West.

In your opinion, what is the relationship between the artistic side of photography and its potential social impact?

A different (artistic) approach helps tease out a type of truth that might not be apparent or present in more mainstream or straight ahead photo projects. How each photographer defines the limits, boundaries and spectrum between fine art and photojournalism is up to them, but I feel honesty and being upfront about one’s choices is an absolute.

Images by © Lawrence Sumulong