Hoda is 33 years old. She lives and works in Australia. One day, she left her country of birth, Iran—a rupture that has forever marked the photographer. She has returned several times since leaving, but for a long while she was incapable of taking photos there. Until “In the Exodus, I Love You More”. In this series born of a wound, Hoda explores her relationship with her country and with absence.

Fisheye: What’s your background with Iran?

Hoda Afshar: When I was living in Iran my documentary work focused on social and political issues. I was especially interested in the lives of individuals and marginalised groups—in parts of Iranian life that were far from my own experience. Photography became a way for me to discover and understand new things. But after leaving the country, it became harder to deal with these subjects. I didn’t feel legitimate in telling other Iranian stories, because I’d left. I think that “In the Exodus, I Love You More” reflects the two sides of this experience. On the one hand, it’s a more personal piece of work that explores my connection with Iran. On the other hand, it questions the ambiguity of representation, which I’ve brought up in my previous work.

You explain on your website that, for you, Iran as a country is poorly understood and often badly represented. What makes you say that? What would you like to say about Iran that people don’t know or see?

I think most people would accept the idea that dominant Western media representations of [my country] reflect the geopolitical relationships between Iran and the West. Despite all that, we can now see a larger variety of images coming from Iran, as its relationship with the West shifts dramatically. What interests me is precisely to understand how its more positive and authentic images are still just as deceptive.

I’ve seen a lot of Western photographers and reporters travel to Iran over the past few years, “revealing” their discoveries—that is, the reality is certainly different from the idea people have of it. As if seeing your ignorance get blown up is something you should be happy about. It’s also very narcissistic, because these reports are often accompanied by a message: Iranians are “okay” because, in the end, “they’re like us”. And vice versa. Many Iranians want to show this Western image of their country, because they’ve got it into their heads that the West is a good model of civilisation. [Stereotypes are spread], signs of an exotic Iran, that feed a domestic imagination of the foreigner. For example, half-veiled women who dress in “Western” clothing… In any case, it’s about presenting Iran as a nation ready to embrace Western consumer culture, while it remains just different enough to seem exotic.

Is there objectivity in your series, in that case?

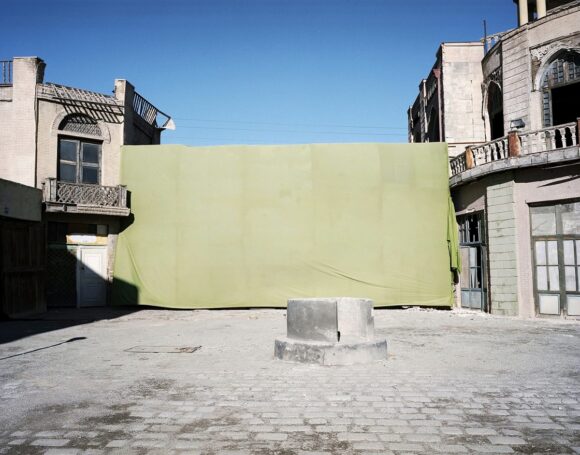

My images reflect my own history with Iran, without a doubt. But my aim is to say there’s no one reality that can be photographed and that my vision will always contrast with another’s. The idea I’m trying to develop in this work is that even if all the images brought together to form a narrative are the fruit of one person’s perception, they’re not necessarily false because of this. It crosses a line when this subjectivity is presented as the sole truth.

When did you leave Iran? How did this departure change your outlook, your way of taking photos?

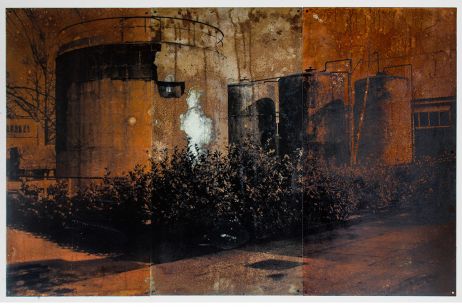

I left Iran almost ten years ago, and even if I go back often, the experience affected me profoundly—personally, and as a photographer. Immigration is something that shatters your universe, that changes your view of the world. The pain of being uprooted brings a very strong feeling of being homeless, of not being in one’s place, and this never totally disappears. It’s an odd existence: the whole world seems like a strange land. I’ve tried to incorporate this fully, rather than hanging on to a nostalgic image of the home, or of exile. Conversely, I like exploring this in-between state as a condition that’s very connected with our times. What’s also fascinating is that things can become so close when you’re far away—and vice versa. Consciously or not, I evoke this a lot throughout “In the Exodus, I Love You More”.

Why do you go back to Iran? How did your series begin there?

I’ve never stopped going back, but for a long time I didn’t take any photos there. When my father died, I felt a sharp need to reconnect with Iran, to explore my relationship with this country through the prism of my father’s memory. He taught me a lot about my country, and, in a way, I wanted to remember him and to honour his memory by taking photos. I didn’t have a very clear idea of what I wanted to produce. It was all new to me. So it was a pretty instructive experience that challenged me a lot, because it became more than just exploring my relationship with Iran.

Who are the people you photographed?

Family, friends and strangers. Faces that caught my eye. Faces that seem to hold a story, sorrow and silent secrets.

How would you describe Iran to someone who’s never been?

It’s hard to say. Iran is a huge country, with different geographies, communities and cultures. It’s a country with an extraordinarily long and complicated history, that always evolves very fast. Every time I go back, and the more I travel there, I realise that even my own understanding is limited. It’s an endlessly surprising place. The foreigners I’ve travelled there with have always been really surprised to learn just how wrong their prejudices turned out to be. This, to me, is a country that’s always questioning people about the basis of their assumptions.

If you had to hold on to just one image from this series…

If I had to choose one, which is very hard, then I’d choose one of the photos that best reflect my emotions at the time I took it. Some of them are the memory of real moments of epiphany. For example, the one of the red and black sand that I took a year ago when I got to the red island in the south of Iran. When I set foot there, I had the feeling of touching the whole universe. It was magical. Another example: when I saw two white horses standing face to face in a misty forest, in the north of Iran. One of them looks like a unicorn. I had the feeling of being in the middle of a dream.

I also really like the portraits in the series. These images were a real challenge to rise to. Sometimes you experience these moments when a face reveals a small secret to the lens, a sort of look or gesture that draws you in and pierces your soul. If I’m lucky and I click right at that moment, then I know I’ve taken a good portrait.

Three words to describe this piece of work?

Passage, surface, absence.

Images by © Hoda Afshar