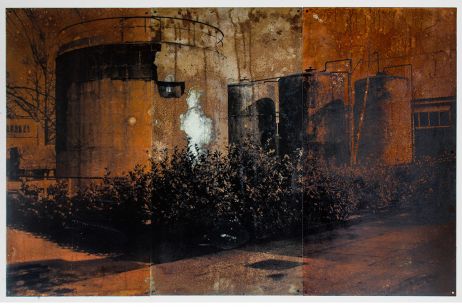

Gentrification is an issue currently at the heart of London’s community. Here, Nicola Muirhead, Bermudian photographer, reminds us the relevance of the negative impacts towards social inequalities that have recently suffocated Londoners. In Brutal Presence is a photographic project documenting the lives and stories from the tenants of Trellick Towers.

Fisheye : When did you first start taking photos ?

Nicola Muirhead : I started taking photos as early as 13 years old with anything available to me, using those cheap disposable film cameras. It wasn’t until 2013 that I started to take photography seriously and purchased my first DSLR camera. Working in my home country, Bermuda, I began to photograph the people I met. It was there that I recognised I had a passion for storytelling. I wanted to use photography as my medium and began freelancing as a photojournalist for a bi-weekly newspaper. I continued on as a senior photographer at the daily newspaper, and the rest is history !

How does your work stylistically lean towards documentary photography ?

My photography constantly continues to evolve and change. I would define my work as documentary in approach and contemporary in style. I started out as a traditional photojournalist and will always have that investigative approach in my research and in choosing my subject. But following my Masters in documentary photography I opened up artistically in my practice and I no longer feel inhibited by a “traditional” approach to storytelling.

How did the idea come to mind of documenting Trellick Tower ?

The idea came to me as a final project during my Masters at the London College of Communication. I lived close by and would often walk past Trellick Tower, always intrigued as to who lived inside. I had no idea I would still be documenting the estate a year later !

Like you said, you would spend more time than expected on the project, so what was your initial intention of documenting Trellick towers ?

Thinking back, I suppose I didn’t have any defined intentions when I first approached Trellick Tower. I knew I wanted to document life within, and around, the estate. Soon I came to the conclusion that this was a far bigger project then I had anticipated and therefore went about meeting residents one at a time to hear their stories.

How did you meet the tower’s inhabitants ? How did they react to you ?

In the most direct way, knocking on doors! They were skeptical of my intentions at first, of course, and I would have to explain myself with an elevator pitch (quite literally in the elevator), attempting to steal their attention or a phone number before leaving the building. Soon I became a regular fixture in the tower, and earned a smile here and there from the security guard who I would leave notes with to ask for potential interested participants in the project. As the months went on I had met eleven residents, and would speak with them regularly throughout the week for pictures and interviews. It was tough, but we connected, and thus the portraits speak for themselves.

You document the opinions of the tenants, but could you say it is more broadly a voice for London?

I would say this project is a voice within a bigger conversation about London’s social housing crisis and the communities that live inside these estates. Each resident I interviewed had a different take on their experience within Trellick Tower – each one has reflected on the changes in their community and have noticed the effects of gentrification. Some have come to peace with the change and continue to hang onto their homes and meet the increase payment of rent, while others consider leaving. Thankfully, Trellick Tower has been protected as a Grade II listed building, which has safeguarded the tower block from private developers that would otherwise decant its social housing tenants and rebuild for private housing. The fact that Trellick has managed to remain 80% council flat tenants is remarkable and a testament that social housing can coexist within the affluent borough of Kensington and Chelsea when properly maintained and looked after.

Did the fire of Grenfall Towers have an impact on your documentation ?

The issues surrounding social housing have always been problematic for a long time in London. People, however, become slowly desensitised to the topic of gentrification for many years and lost interest in this crisis, perhaps feeling powerless do anything about it. The devastating fire at Grenfell Tower awakened the London community again to the reality of this imbalance between the rich and poor, recognising that enough is enough. So for me, the documentation of Trellick Tower – and future social housing blocks – became even more pressing.

Is this a subject close to heart ?

I think it would be impossible not to feel close to this subject after working for a year interviewing the council tenants of Trellick Tower. When I began the work, I didn’t have a lot of knowledge about the housing crisis here in London, and being drawn to the building connected me to a community that I wouldn’t have otherwise encountered. There is a diverse and unique world within Trellick Tower, not dissimilar from many other tower blocks in London, and I learnt that those individuals make up an important part of London’s urban fabric.

Have any other photographers inspired you for this series ?

Dana Lixenberg and her series Imperial Courts was a huge influence on the work. I really admired the way in which she involved the residents and the fact that her project was a documentation that spans over twenty-two years. She immerses herself in the community and established a sincere trust with the tenants.

What is the link between text / photography in your series ?

It was really important for me that this project was a collaboration between myself and the residents. I am an outsider coming in – and I wanted the viewer to have a real insight into the diverse perspectives and realities that exist within Trellick Tower. Therefore, it was an obvious conclusion to incorporate their interviews as captions to the images. Having the interviews written out forces us as the viewer to take the time to read them – somehow there is more weight in reading a testimonial in black and white text.

Finally, What is your favorite picture ?

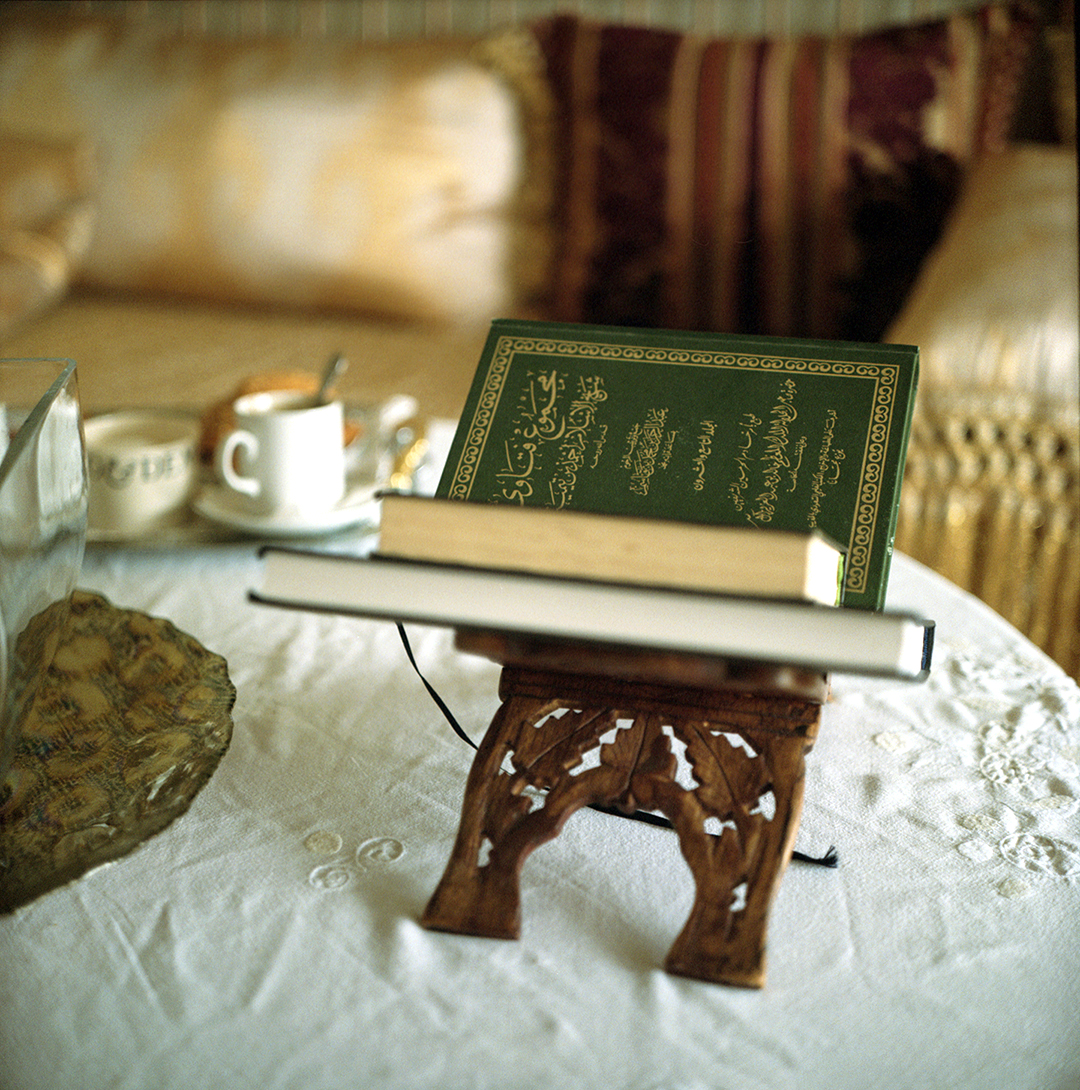

I would have to say the most meaningful portrait is of Edith. Edith is the oldest resident in the estate. She migrated to London from Jamaica when she was in her early 20’s and became a nurse soon after moving into Trellick. Her apartment is almost exactly the same as it was when she moved in – all the yellow wallpaper and the 70’s tiling in the kitchen has remained. I remember looking at the photographs of her when she was young in her nurses outfit, standing in the living room that had not changed. It took a long time for Edith to trust me but eventually she got used to me being there and let me start to photograph her. The portrait I finally caught of her was in the moment that she looked at the clock on her wall – a clock that is in fact broken – but she would often stare at it regardless. Perhaps it is a symbolic image of lost time and the uncertainty of the future for these social housing estates.

Photos by © Nicola Muirhead