After her father’s death, photographer Ioanna Sakellaraki travelled back to her home country, Greece, all the way to the Mani peninsula, looking for representations of mourning. In The truth is in the soil, an abstract story inspired by Greek laments, she questions the notions of absence, presence and fiction facing a mysterious entity called Death.

Fisheye: Who are you?

Ioanna Sakellaraki: I am a Greek, London-based photographer. I’ve studied journalism, photography and cultural studies. My photographic practice revolves around memory and loss and is strongly connected to my homeland Greece, which owns an archetypical aura and ambiguous place in my heart. My images suggest a constructed space of fantasy and loss within the magical potential of transformation and fiction the camera allows.

To what extent has photography influenced your life?

It has been a slow-paced journey. I have been living abroad for the last decade. I left Greece soon after I turned 18 and lived in about 7 different countries in Europe since then – while studying and working. Although photography has always been a big part of my life, my studies had pushed me towards another career. Yet, photography was never a hobby, I was making time and space for it until I made the choice to put on hold everything else. I would say that it takes a lot of hard work and energy – it has to become your life for it to change you. At least it did with me. I have learnt to be more patient and resilient, more curious about the world around me and to be honest a lot more excited about life.

How was your series The truth is in the soil born?

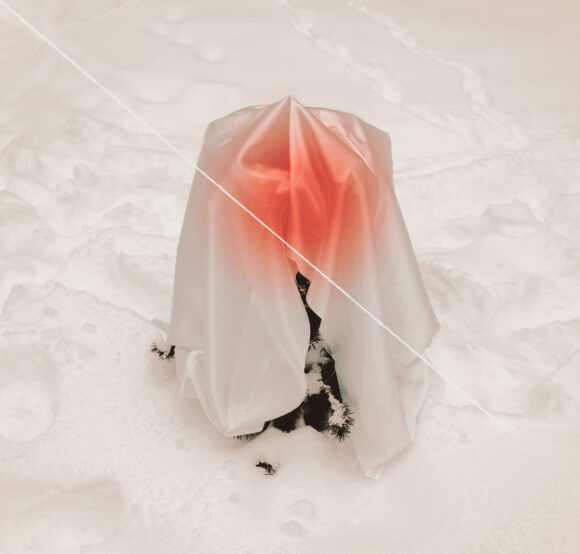

After my father passed away 3 years ago, I returned to my homeland, Greece, and followed in my mother’s footsteps, seeking shelter in our religious traditions and cultural beliefs. Photography imposed itself as a way to deal with loss. I am interested in how the image asserts things in their disappearance and gives us the power to use them through fiction. The pictures themselves lay between real and unreal allowing the viewer to believe in another type of reality.

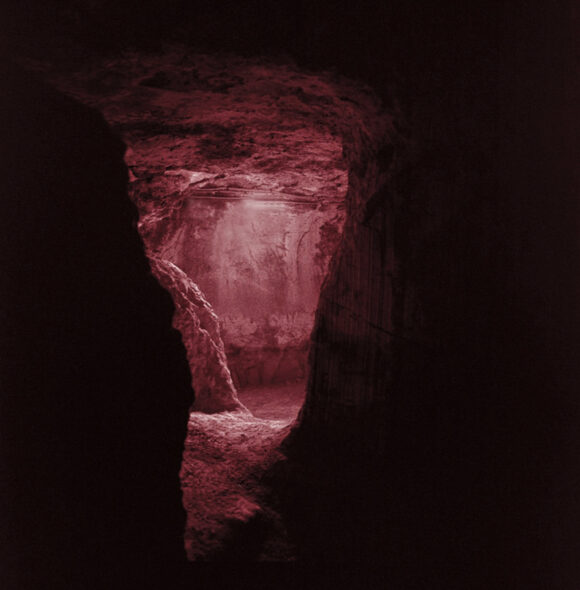

As the project advanced and inspired by the origins of ancient Greek laments, I dwelled within traditional communities of the last female professional mourners inhabiting the Mani peninsula of Greece looking for traces of bereavement and grief. They are the veiled figures in my series.

Who are these mourners?

While most know Mani for its breathtaking cliffs and coastal villages, it is also home to a tradition of ritual lament dating back to ancient times. Considered an art, ancient Greek laments may be traced back to the choirs of Greek tragedies, in which the principal singer would begin the mourning and the chorus would follow. Over the centuries, it became a profession exclusive to women. Those who were especially adept at this improvisation, and could endure the physical and emotional trauma of the work, were hired by families to lead in the ritual lament. Today, the aging of these villages and the current economic woes besetting the country seem to be part of the reasons for the disappearance of this dying art. The truth is in the soil evolves like a Greek myth about life and death, contextualising the idea of mourning in the wider field of Greek drama and psychology.

In what way is the notion of space important in your series?

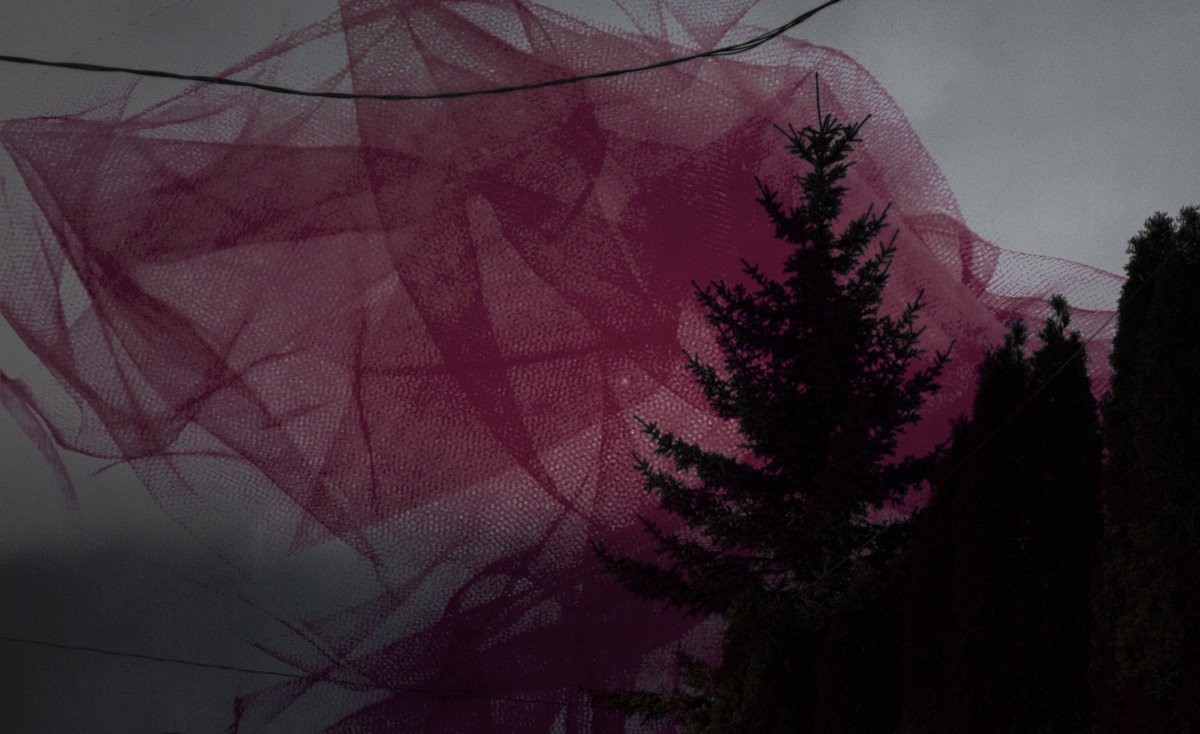

The notion of space has always been a substantial part of my work, but has started to turn into a more personal entity. In this project, death itself becomes a space, the human figures of the female mourners turn into the landscapes themselves – an amorphous entity obeying to its own laws. To a certain extent, this frees me of the time of here and now and the world as it is. Greece may be a constant source of inspiration, but the way I capture it is imaginary. I like this idea of this homeland being this place you know outside of memory, being reborn every time we go back there.

The series plays with the boundaries between dream and reality. Why?

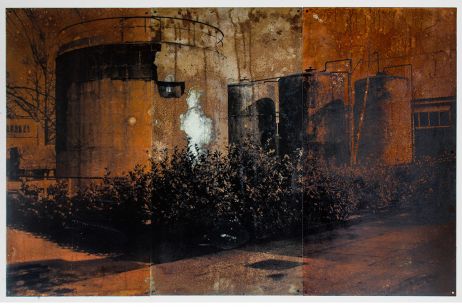

Finding real people and taking their picture helped me connect with that land and get grounded to reality. However, making a work about grief requires a journey through memory and memory loss. I wanted to talk about what is lost: parts of memory that were reconstructed just like the image of a lost person is in our minds, after he is gone. So it becomes a fiction.

I also wanted to integrate death rituals in my series, without necessarily documenting what happened during them. So, I’ve worked hard on finding ways for these images to tell something further than their subjects: a space where time can lie and death can exist. I do not aim at moving towards a surer word but rather break bonds that unite the images with the world as seen, detach them from their origin and create a new visual language.

Your work evolved towards abstraction. Is death an abstract concept to you?

In my work, I approach death as an open-ended enigma with both subjective and objective interpretations, using my images as passage ways between sheltering something from death and establishing a relation of freedom with it. I used symbols as my starting point: what is unknown to us but not completely foreign, to speak about death as a force eating away the visible. In my practice, I seek to develop a language of thought emerging as some type of fiction, becoming all together an impossible image which can only exist in doubt of its own existence and cannot be fully formed but after its very death.

Did you family play a part in your project?

My project was born when I started to question the role of photography in the morning process. Closer observations within my family and culture, created a space for images to emerge. Photographing my family – my mother especially – was something new to me, so was grief, so I treated them both in the same way. My mother became someone I tried to understand, this mourning figure that to some extent was also myself. The images were pushing me to not only encounter my relationship with my family but also my culture and country itself. Gradually, Greece was becoming that mourning figure, a land of curiosity where death was an encounter through family, religion, mythology and the self.

© Ioanna Sakellaraki