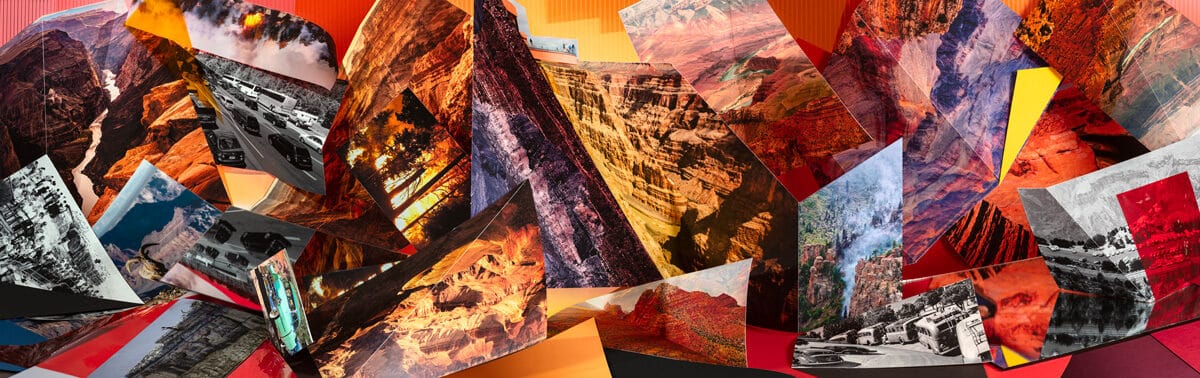

Russian photographer Anastasia Samoylova builds, with Landscape Sublime, an abstract and cubist environment, made out of images taken from databases. Through these dynamic and colourful creations, she questions our perception of reality, and of emblematic sites, at a time when the constant flow of information affects our ability to apprehend the world.

Fisheye: Who are you?

: I am an artist and photographer based in Miami. I work between observational photography, studio art, and installation.

How did your series Landscape Sublime come to life?

I grew up in Moscow, in one of its typical tall grey apartment buildings – not the most picturesque environment. Going out in nature was always a special occasion. Back in Moscow I also discovered online image sharing via Flickr and spent many hours in the day transcending the limits of physical space by looking at the vistas from remarkable faraway places. I started noticing patterns in how the most visited places get photographed, and how those images are subsequently digitally edited in a similar manner and I took an interest in those typologies. After a few years of thinking about it I started visualising my thoughts in physical form in 2013 when I made the first Landscape Sublime.

In this project you use copyright-free images, do you consider yourself a photographer or a visual artist?

Indeed, I use copyright-free and creative-commons licensed images from various online image sharing archives. I’m interested in the images that are meant to be used by others, so it’s not about appropriation in this case. In terms of definitions, I prefer the freedom of the avant-garde of the 1910s and 1920s when artists freely moved between media and had no set titles.

Why did you decide to focus on landscapes?

Initially I started using landscapes as an homage to the 17th century philosophers using examples from nature to illustrate the aesthetic categories as they were being formed, such as the picturesque, the beautiful, and the sublime.

But I was also drawn to landscape because it is intangible; it is neither an object, nor a person or a portrait; it is something that cannot be possessed, only in pictorial form. However, the real subject of the project is the act of photographing, and what it means when there are multiple images of the same kind produced by different people, not landscapes per se.

You stated that you deconstruct the “idealistic iconography of landscape”, what does it mean?

There are certain criteria that seem to be applied to picturing scenic views. I believe in photography it comes all the way from the conventions set in Romanticist paintings; those conventions are in our shared collective memory. All it takes is to browse some popular image sharing platforms under the keywords by the place’s name and compare them to the paintings.

In the case of the more recent landmarks one could compare images to each other and find compositional similarities besides the main subject.

You’ve consciously let some flaws visible in your work. Why?

Those obvious studio signifiers are a gestural metaphor for the constructed nature of any photographic image. A reminder not to take a realistic looking depiction at face value, but rather remember that it is someone’s subjective view and what you see has been constructed for you by the image-maker.

My tableaux are deliberately theatrical for that reason. The goal is to emphasise the set’s geometry and the printouts themselves.

Landscape Sublime is reminiscent of the cubist movement. Who inspired you?

I was originally trained in environmental design and painting and only came to photography later. My main influences are the “Amazons” of the Russian Avant-Garde: Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Varvara Stepanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova. About a year into working on Landscape Sublime I realised how my cubist compositions were really a contemporary version of constructivism, the semi-abstract kaleidoscopic tableau reflective of the time as tumultuous as it was during those artists’ lives.

You question the relationship between photography and reality. Why?

Yes, because I think reality is a very subjective concept, there is no one reality for all – so I’m trying to show that phenomenon with my decidedly constructed, cubist images. I also think that in the era of pictured reality, particularly with its abundance of easily shared imagery, our understanding of the world tends to be shaped as much by the images in their widest sense as by our firsthand experiences of the world.

What is your vision of contemporary photography?

I actually have a fairly lowly view of contemporary photography and find most of it derivative and redundant. The act of cutting up pictures can be cathartic. At the same time, I’m deeply curious about and invested in observational photography that exhibits the awareness of its own methods of creation and its history; what I could best describe as informed photography.

How will you continue to develop this concept, launched by Landscape Sublime?

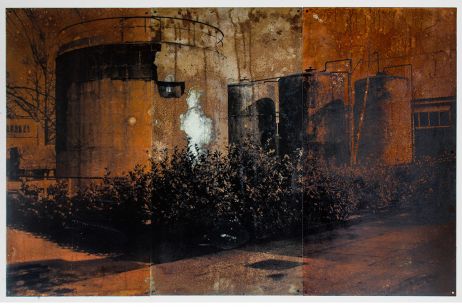

I’ve expanded the ongoing Landscape Sublime series into a few sub-categories, such as Metropolises and Nature Reclaims. From a compositional perspective, the Metropolises are an homage to Paul Citroen’s famed Metropolis collage from the 1920s. These tableaux are comprised of the printouts of various disasters affecting the familiar landscapes, whether it is wildfires or floods, documented by people in major cities.

Would you say your work has an environmental dimension?

I think the fact that there is already so much imagery of these not so natural disasters online is an alarming testament to the rapidly heating climate. As we know, cities have a lot to do with climate change and yet cities are where the solutions for it would be coming from. During the Covid isolation there were many news stories of the return of animals into their habitats lost due to human pollution, such as dolphins appearing in Venice. Some of this news was debunked as fake, others were eventually proven true. In the time of crisis when everything seemed out of (human) control it felt so uplifting to see the evidence of non-human life thriving, albeit temporarily.

© Anastasia Samoylova