Fisheye: You mostly photograph women, why?

Vincent Ferrané: We are, I think, living an extraordinarily important moment in the history of gender, its representations, its deconstructions. These questions move me, as a photographer. The medium de facto showcases a certain mode of representation of beings, and their relation to the world. How then, when one works with imagery, can they integrate these elements without using ancient models? How to highlight all the recent changes without tackling their paradoxes? Can one deconstruct the archetypes without negating their history?

I wanted to integrate these questions into several series and books. In every one of my projects, female figures – ever evolving – are shown, and through them I try to find my own place, as a male photographer. For Milky Way, I’ve captured my partner and our child, during the unique period of breastfeeding. In Visitor, I’ve documented women artists and their creative routine in their studio. And through Iconography, I’m studying the codes of beauty of a fashion icon. I’m also working on different projects tackling the same issues without showcasing only female subjects.

What was the genesis of Iconography – 25 figures of Jeanne Damas?

We are only starting to grasp the power social media hold over us. The messages conveyed by these networks must be understood correctly. Nowadays, we are consuming more and more images. Some are the results of active research, others are fed to us passively. But they are never trivial, they always carry hidden meanings, and – regarding the body – hold a political dimension. This is what I’m interested in. To sum up, let’s say that images reveal symbols that are not always questioned, and often thought as natural, but they are the result of an everchanging history.

What gave you the idea to work on canonical beauty?

Beauty, visual beauty is structured by different things: notions, codes, aesthetic, psychological, cultural and social thoughts… History is punctuated by changes – sometimes drastic ones – showing that beauty is never the same and often fits a given period. The notion of ideal varies, only normality remains.

To produce this series, I wanted to investigate the appearance and representation of beauty. I wanted to picture it as a construction, a combination of sublime and mundane elements, blending together to form the jigsaw puzzle of a potential “beauty”. I focused on details that became archetypal as they kept popping up throughout history.

Regarding the word “canonical”, it is linked to the idea of rules. According to the treaty written by sculptor Polykleitos, the “canon” is defined by a symmetrical body with harmonious proportions. Though the treaty is incomplete and has been reinterpreted, I wanted to use these notions – or rules that became laws. I chose to question them by using an incarnated figure who has – successfully – mastered these different rules.

Could you tell us more about the title of the series, and this notion of iconography?

I’ve tried to combine two meanings of the word “iconography”. The first being associated with a collection of images, while the second evokes the figurative representations of a subjects, and so the construction of an icon through imagery. A construction borrowing – through its dogmas and directives – from religious models and profane arts.

Jeanne Damas is not the only it-girl/model/businesswoman who succeeded, why her?

As a model/it-girl/influencer and businesswoman running a clothing and cosmetics industry, Jeanne Damas is an emblematic figure. She embodies an ideal of beauty and success. She showcases a perfect or idealised woman, strategically using the stereotypes of seduction to draw her own outlines. She was on the cover of both economic and fashion magazines. Her Instagram accounts is followed by 1,2 million persons. All these achievements confirmed her fashion icon status, as acknowledged by fans and medias.

Jeanne Damas followed a progressive development until she became an autonomous figure, sometimes described as a “Parisian”, sometimes as a globally renowned “French girl”. She represents a character who draws from an iconographic myth beyond the world of fashion or a celebrity lifestyle.

What fascinated you, in her persona?

She is a professional. Whether I agree or not with the imagery broadcast or its construction paradigm, she generates a form of idolatry, is followed by a fan club – mostly feminine. Thus, I tried to produce a collection of pictures that a Jeanne Damas’s admirer would gather.

How has this collection evolved?

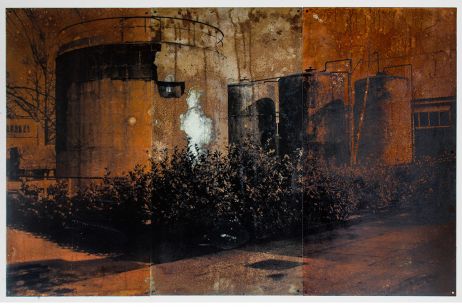

As a public figure, Jeanne Damas is a woman with realistic characteristics who lives a somewhat surreal life – from her followers’ point of view. In this series, I wanted to gather clues, scraps of materiality, fractioned and incomplete images.

This series is composed of what a Jeanne Damas’s fan would collect. Someone who’s keep everything coming from her. What would they seize, collect, keep from their idol? They could, of course, mimic her gesture, her clothes, her style, but they could also take things further and try to learn more about her identity – with her passport, the digital prints left in her mascara, a strand of hair… They could scrutinise her destiny in her palm, or even keep a lipstick-stained cigarette butt.

How did the collaboration go?

The photoshoots were scripted. I would come over with a mood board filled with images from Jeanne’s Instagram feed: pictures of parties, of photoshoots where she poses for her own brand, excerpts from beauty tutorials, her favourite objects… And some iconic and historical examples that seemed to be referenced. I would then let Jeanne interpret her own public persona.

What were you inspired by?

Jeanne Damas’s character seems to be the mixture of several female figures, from classical painting, to the femme fatale of 1930s Hollywood films, from pop art to beauty tutorials. I enjoyed sort all these out and get inspired by my references to build a series revealing more or less known parts of my model.

For example, the Odalisque (a female attendant in the household of the Ottoman sultan), cut in 3 parts in my pictures, is inspired by poses that Jeanne posted on Instagram. They always remind me of the odalisque painted by Renoir (1870). The way she presents her clothes in catalogues is borrowed from the classical Contrapposto – an art technique designing poses where hip-lines and shoulder-lines are reversed. Silhouettes that can be found in the classical representations of Venus, for instance.

Any modern influences?

When I created the cigarette picture, I had Les cigarettes by Irving Penn in mind. Some objects that I used, like the eyelash curler, could be linked to the series Beauty of the Common Tool by Walker Evans (published in 1995, in Fortune magazine). But here, the chosen tools all help enhance beauty.

Regarding the method, I was inspired by writers who wrote feminist critics of the popular culture. Like Laura Mulvey, in Fetishism and Curiosity, 1996, who was trying to define our cultural collective subconscious. She wrote, about Pandora’s myth, “how much our get-ups – forging the fascinating power of women – are associated with artifice (makeup, cosmetic products, style), and how Pandora’s ancestral origins, before the birth of a consumer’s society, show the depths of the images of feminine seduction as artifice and illusion.”

Was it hard to work with an Instagram celebrity?

I guess things may become difficult if one tries to distance themselves from the “safe space” of an Instagram celebrity. But I wanted to work on these elements, this visual language she uses on social media, as closely as possible. This series subtext? Beauty is a construction. I didn’t want to simply deconstruct Jeanne Damas’s character to present a laborious backstage experience. I’m more interested in the construction of beauty itself, through an emblematic character perceived as beautiful.

Why the use of black and white?

This hardly contrasted black and white – almost grey – creates a sense of distance, in opposition to the shiny and colourful effects of images and series in which a figure like Jeanne Damas is supposed to appear.

Any anecdote you’d like to share?

Jeanne Damas smokes roll-ups – faithful to her free French girl persona. But, as an influencer, she cannot promote tobacco – especially given that she’s followed by young, anglophone people. As they discovered these images, many fans were choked: how is it possible to still smoke, in this day and age?

Was there one picture that stood out to you?

I like many of them, but I designed this series as an assembly of pictures, a way to create a portrait through touches, details, gestures and objects. Each viewer is free to rebuild, or to try and imagine the result of this jigsaw puzzle.

Three words to describe Jeanne Damas?

Jeanne knows what.

And about the project?

“Who are you, Jeanne Damaggoo?”

A work to discover in the book Iconography- 25 figures of Jeanne Damas :

Iconography – 25 figures of Jeanne Damas, Libraryman, 40 €, 52 p.

© Vincent Ferrané