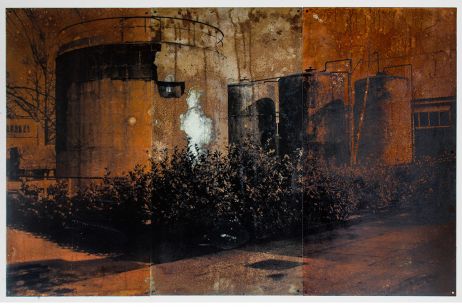

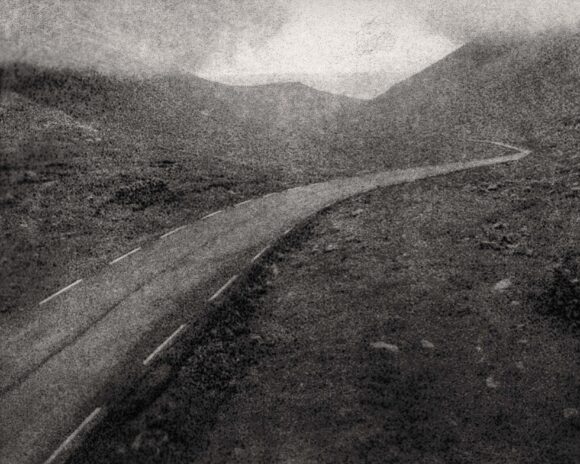

Marcus DeSieno is fascinated the progress of technology and its impact on our world. To create No Man’s Land: Views from a surveillance state, he hacked into surveillance cameras, looking for deserted landscapes from all around the globe. Interview with a committed artist.

Fisheye : Have you always been interested in technology?

Marcus DeSieno : I’m particularly fascinated with how photographic technology and optical machines have fundamentally altered how we perceive the world. In my work, antiquated and obsolescent photographic processes and media are often combined with contemporary imaging technologies to engage in a critical dialog. Because the camera – this machine – has forever changed us, all of us. The invention of the photographic medium created an immutable shift in human perception.

Could you explain to us the concept of No Man’s Land: Views from a surveillance state?

In our increasingly intrusive electronic culture, how do we delineate the boundaries between public and private? My series seeks to interrogate how surveillance technology has changed our relationship to landscape and our place in the current geopolitical climate. To produce this work, I hacked into surveillance cameras, public webcams, and CCTV feeds in pursuit of the “classical” picturesque landscape. The resulting visual product leads to an investigation of land, of borders, and power. The very act of surveying a site through these photographic systems implies a dominating relationship between man and place.

What did you want to highlight, through this series?

How can we move forward as global community to address issues of clandestine surveillance and government abuse? Questioning the pervasive nature of surveillance is an essential conversation in No Man’s Land, I hope to undermine these schemes of social control through these photographs—found while exploiting the technological mechanisms of power in our surveillance society.

Why calling it a No Man’s Land?

I liked the idea of a disputed and undefined space and I think these photographs fall into this category. Images conjured up in the mind when one hears the phrase “No Man’s Land” are barren, empty, desolate landscapes. The term is most famous for the unoccupied trenches and territories between armies during World War I, but the larger idea that a space remains unoccupied due to fear is enticing. The uncertainty of how this surveillance technology has altered our society and understanding of landscape, the uncertainty of how we relate to and consume nature in the digital age. We are currently, as a civilisation, already standing in the middle of this No Man’s Land.

How did you hack into those cameras ?

When I found out how many cameras we have out there around the globe I knew I wanted to see what I could do with them. The project took time – there was a fair amount of research and a fair amount of thought put into the parameters of the project. How should I use these tools to add something to this conversation about surveillance, do it in an ethical way? I had no previous experience, but I can tell you it was shockingly easy. And it was certainly terrifying to find out that this was so easy. I started with a simply google search “How to hack into surveillance cameras” and I was globetrotting around the world from my computer within the hour.

How did you edit those pictures, afterwards?

I photographed the screen with a large format camera using a waxed paper negative process. This is a means to insert my hand as artist into these images and to obfuscate the pixelisation that occurs naturally from these lo-resolution cameras. I have a lot of experience with 19th century processes. I worked at an atelier that specialised in 19th century processes out of university and different material photographic processes have always been central to my work. By hiding the digital origins of these images through this process, the final product becomes dislocated from its origins and gains a sense of timelessness that creates a more complex reading for the viewer.

Why did you choose to focus on landscapes?

I’ve always been attracted to landscape. I’ve long been consumed by the mythologies of the American West – these iconographic images of an untamed Frontier. I’m obsessed with collecting stereo views from the geologic surveys of the time; invitations to the masses to come and settle and consume the land. To me, the focus on landscape seemed far more interesting then focusing on the intrusion of people in their private spaces or lurking on the street corners in a sea of urban sprawl. There are many artist doing just that with similar technology. Landscape already has in it embedded ideologies of conquest, ownership, voyeurism, and consumption. Why not use this history as a grounding point to create another vector in which we can critically examine the implications of surveillance technology and its effects on how we perceive and interact with the spaces?

Why did you decide to publish a book of the series?

I have been asking myself lately what my social responsibility was as an artist. It is not a question I’ve figure out, but perhaps the desire to create this book came from these ethical battles inside of me. The conversations about how we use this technology in 2018 are of the upmost importance and will continue to be in the future. Can my artwork force the viewer into a space of introspection or action? Perhaps – perhaps not, but I feel I have an obligation to do something.

© Marcus DeSieno

No Man’s Land : view from a surveillance state, Éditions Daylight Books, 38€, 112 p.