Irish photographer Rhiannon Adam spent three months in 2015 in the Pitcairn Islands, located in the middle of the Pacific. She investigated particular social drifts caused by its insularity. An immersion in myths and isolation. This article can be found in our latest print issue (March – April 2019).

Pitcairn, the only overseas British territory in the Pacific Ocean. Amongst the four islands of a surface of 47 km², the island shelters nine families, or around fifty inhabitants. Most of them are descendants of the revolts of the Bounty, a British ship sent in mission in 1797, and of their Polynesian wives. In 2004, more than two centuries later, a scandal breaks out from the territory: seven men, including Steve Christian, the mayor of Pitcairn, are accused of more than 55 sexual crimes including sexual assaults on minors.

Correcting the silence of the past

Fascinated by the stories, Irish photographer Rhiannon Adam travelled to the island in 2015 and became the first person to document this edge of the world. “Was I capable of working in such a place? Would I be able to understand the locals of the island? I wanted to not only photograph them, but also shed light on certain aspects of human nature”, the artist explains. In order to cover this story, she had to get out of her comfort zone. “I made this project a personal affair”, explains Rhiannon Adam , who, in her childhood, had herself been the victim of sexual assaults. Therefore, this trip to Pitcairn became a sort of therapy, a chance to reaffirm herself again and to “correct the silence of the past”, according to her own words.

Visa in hand, the photographer loaded on the New Zealander cargo ship MV Claymore II, the only one disembarking at Pitcairn. “I stayed on the island during the complete rotation of the ship, which lasted three months, she says. I wanted to take my time. I was there to experience claustrophobia and conduct a project that would answer my questions. There was room for only nine people on the ship; Pitcairn locals were given priority so I was unsure of embarking. My ticket cost 5,000 dollars and my nights on the island, 100 dollars.” Personal or medical emergency, broken cameras or unforeseen events… Rhiannon Adam had no escape plan.

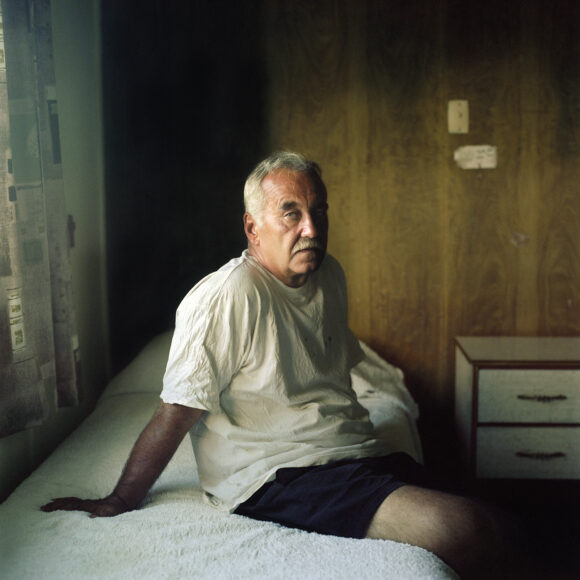

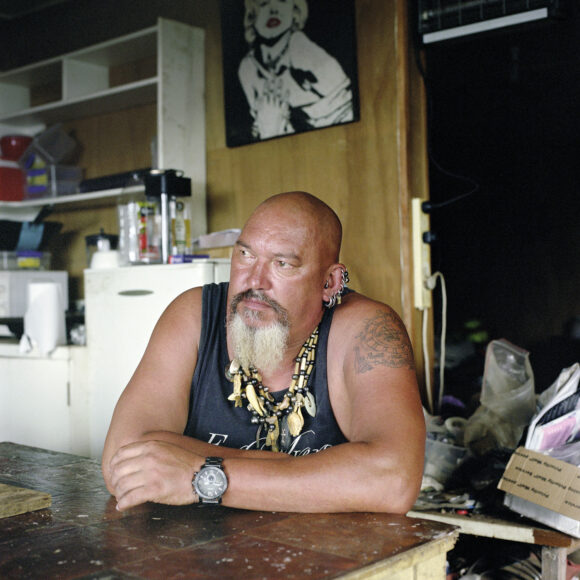

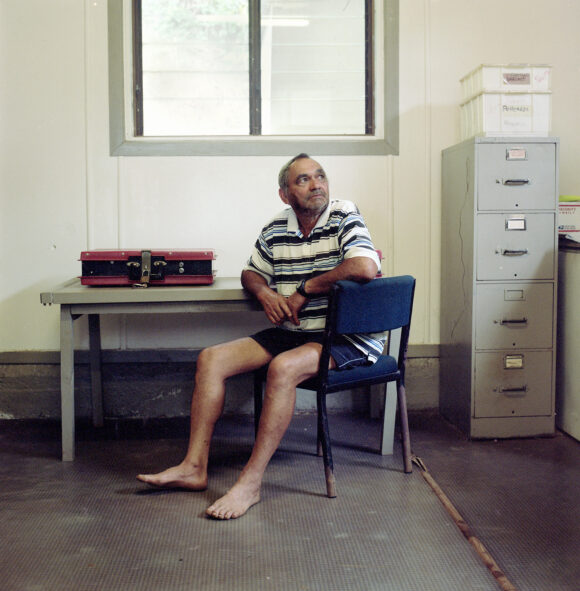

Once at the island, the photographer encountered reluctant residents and spent most of her time trying to integrate the community. “I offered my services and went to church even though I am not religious. I never found my place, and the locals themselves did not know how to place me. It took me a while to convince them. Most of them wanted their contribution to the project to remain secret. I did not succeed in photographing everyone”, she specifies. Finally, the ones that do not appear in the project are the ones who told the most intense stories. Why did they prefer to stay in the shadows? What were they ashamed of? “If people had been nicer, more open, if I had felt more welcomed by the community, it would have showed through my pictures, the photographer confides. Maybe they knew things I didn’t: the only possible story was one of sadness. I do not think people liked seeing their negative facial expressions exposed to the eyes of others.”

A forensic universe

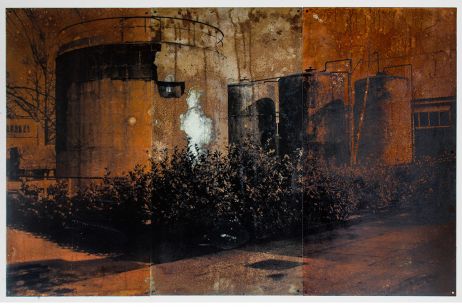

Fascinated by Polaroids, the author tried to compensate for a lack of memories through her photography. “I went to Pitcairn because of my passion for expired film rolls. I needed a big project to use the rolls I had patiently collected”, she explains. The use of the instantaneous emphasised the ambiguity that characterises the island. Although her worn film rolls symbolise fragility and misery, they also evoke magic and past mythology. “The series Big Fence/Pitcairn Island is a rendering of a portrait of invisibility. The Polaroid tells a story through its chemistry, its relationship to space and to myself. I used this expired film to draw a parallel between a dying community and its abstract and blurry existence. It also represents my own memories fading away.”

In Big Fence, the Polaroids are associated with film camera pictures and archives as to assemble an even more ambiguous story and to avoid tilting towards an unwanted romanticism. “I wanted to create a forensic universe, since it was all about demystifying the myth”, the photographer adds. Rhiannon Adam never had the intention to document the after-scandal, but sought instead to study how notions of utopia and romanticism had led the residents to lose their minds and their sense of reality. Why do some consider Pitcairn a paradise, while some see it as a nightmare? How did Pitcairn disable the moral compass of its inhabitants? “It’s as if we wanted desperately to believe in the existence of a garden of Eden. We all want to believe in fiction, myself included. And when we open this Pandora box and understand the horrors hidden underneath the iceberg, we instantly want to close it and pretend it never existed”, the photographer continues.

This article is an excerpt from Fisheye #35, available in newsstands or here.

© Rhiannon Adam