Sanitary installations built during the hygienist period, lustful meeting places where bodies let go and fantasies are created, symbolic spaces for the liberation of an oppressed LGBTQ+ community… Public urinals are emblems of the social and sexual practices of the 19th and 20th centuries. An invention that the photographer Marc Martin placed at the heart of Les Tasses, Toilettes publiques, Affaires privées (Public toilets, private affairs, ed.) An encyclopedia rewarded by the 2020 Sade literary Prize, paying homage to these dens of iniquity, where acrid human smell blends with tabooed desires.

Fisheye: What is your vocation as a photographer?

Marc Martin: My gaze goes to the contours of the private sphere. To the way bodies are portrayed in the public space. To minorities. I try to widen the circle of tolerance, including within the LGBTQ+ circle.

How would you define your artistic approach?

I would say that my photography is a resistance to an aseptic culture, to oxidizing freedoms. It thumbs its nose at the “legitimate gaze”. In my opinion, evoking intimacy is revealing a secret zone hidden in the shadow of public and polite representations. I am not trying to make the viewer like what he sees in my photographs. I let him discover my taste for liberated sexuality, freed from boxes and shackles. Between poetry and pornography, dirty men and flowers blend together well in my images.

Is it this contrast that pushed you to conceive Les Tasses?

Yes. And then, the imaginary on the margins, the interstices have always attracted me. The vespasienne, built at the time of hygienism, had to respond to natural needs. It responded to a social one. So many encounters against the norm were played out in these public places. Repositioning social and sexual practices at the heart of the aedicule is my subject. What interests me is less the act itself than the determination it implied and the energy it engendered.

Where does this title – Les Tasses – come from?

“Faire les tasses” (“Making the cups” in English, ed.) in the slang of the 19th and 20th century was to “dredge around the pissoir”. An expression no doubt inspired by their teapot-shaped frame. The expression disappeared from the language, and the vespasienne from the pavement, but at the time there were some on every street corner. The vespasienne symbolises at the same time the first element of urban furniture and the ancestor of meeting applications. It is a part of urban history that has always remained hidden in the name of decency.

Your book is a true encyclopedia. How has this project evolved?

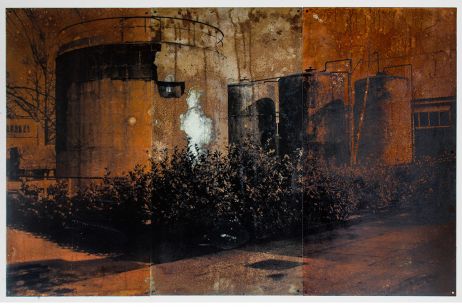

It is a work of introspection that mixes artistic vision and historical research. This project goes back about ten years. At the time, I was exploring abandoned places for a photographic series on urban ghosts. I slipped inside an old pissoir. I knew they had been closed for decades because the graffiti on the doors of the cabins dated from the 1980s. Their authors may have disappeared, but the traces of their fantasies had remained there.

By photographing these graffiti, I was thrown into another era, where men seeking to meet other men often had no choice but to find themselves there, out of sight, in the anonymity of the pissoir. One of my series, Paradis perdus, illustrates, like a forgotten heritage, the architecture of these abandoned places.

To carry out this project, you did a lot of research. What did you learn?

I discovered – beyond the stories of morals – that the vespasiennes were a place of exchange and meetings during the Resistance in Paris. That they served as an observation post above the Berlin Wall during the Cold War. That they were the object of the first feminist demands for equal treatment.

Public urinals, diverted from their initial use, played a capital role for “generations of men in the closet”. In an environment hostile to diversity – homosexuality was penalized in France until 1982! – it was not common to display one’s inclinations in broad daylight at the time. They had to be satisfied in secret. The walls of les tasses furtively sheltered these men with desires condemned by the law. These places, however stinking and cramped they were, were spaces of freedom. Out of lack for anything better.

You’ve made the choice to represent the LGBTQ+ community in a very intimate way. Why did you choose to do so?

This is an uncomfortable subject, even for some part of the LGBT+ community. Was it necessary to say everything, to show everything at the risk of offending good sense, of provoking embarrassment or disgust? Are these old meetings around the urinals compatible with the respectability aimed at by some spokespersons? These little stories in the shadow of history are part of our past. There is no shame in telling them. The society of the time confined these meetings to sordid places, so they could pretend to be unaware of what was going on. Les Tasses explores the question of otherness in the city and the development of identities.

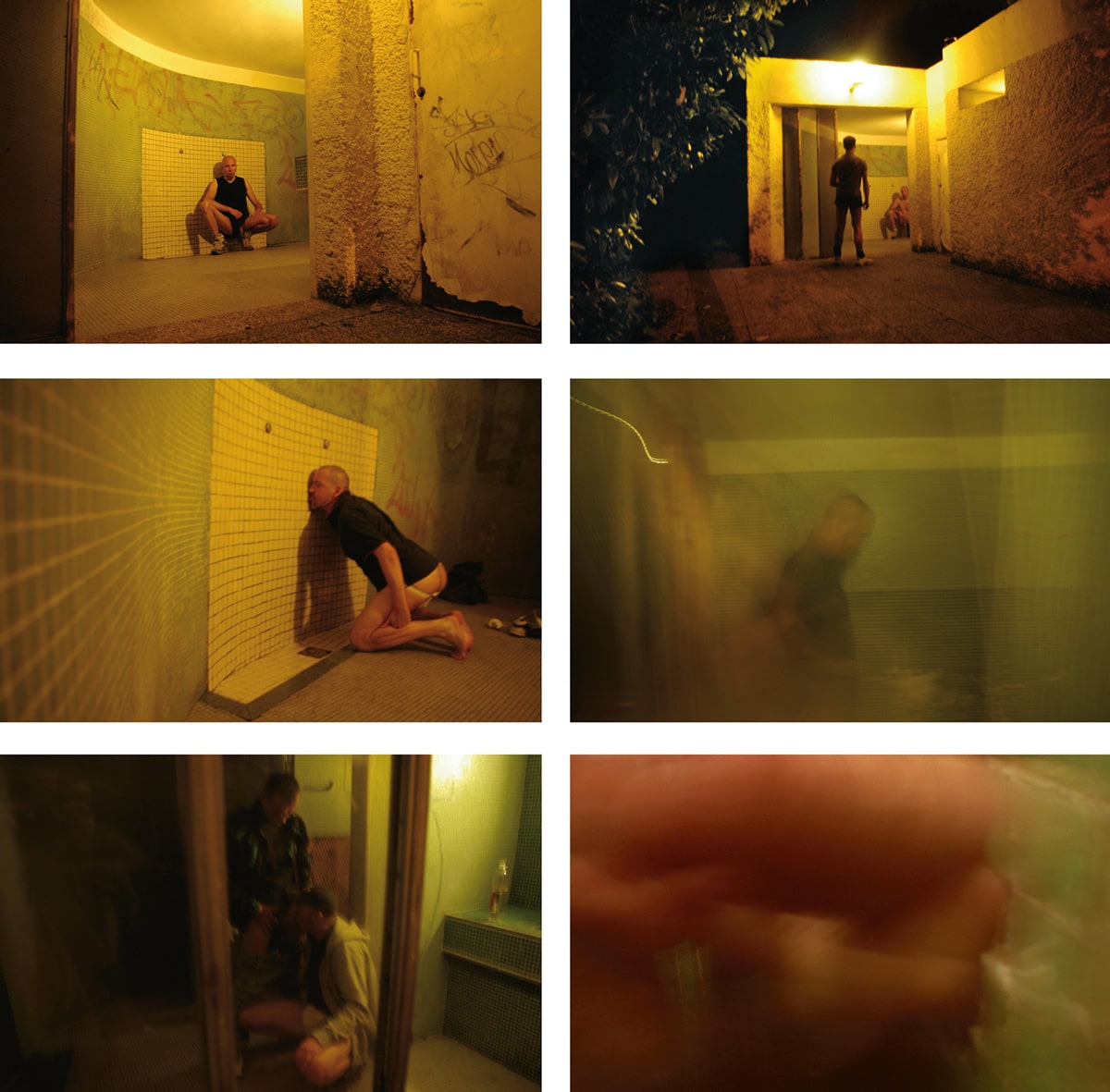

How did the shootings go?

Synonymous with sexual misery for some, an attack on decency – even morality – for others, encounters in these tasses are full of prejudices in the collective memory. So, I wanted to play with codes. For if it is not embellished, the memory of a bygone era will be lost. I wanted my images to be obscene… of enchantment. Yet the places were dark, dirty, narrow, unlikely to be photographed (old underground urinals in Berlin, the last Vespasienne in Paris…). I invited models to pose figuratively, like a fashion shoot. Then, I asked them to improvise spontaneously to make the situation realistic. From then on, a playground was drawn in real time. The language of the protagonists became fashionable, corporal, social and cultural.

Who are your models? How did you lead them?

They embody diversity in a place of passage. They didn’t know each other at the beginning of the session. Not all of them were gay. Not all of them stayed. Others, non-binary, improvised at the urinal. They were not there to play a preconceived role. They had carte blanche. I didn’t focus below the belt, but I didn’t crop anything, nor anyone…

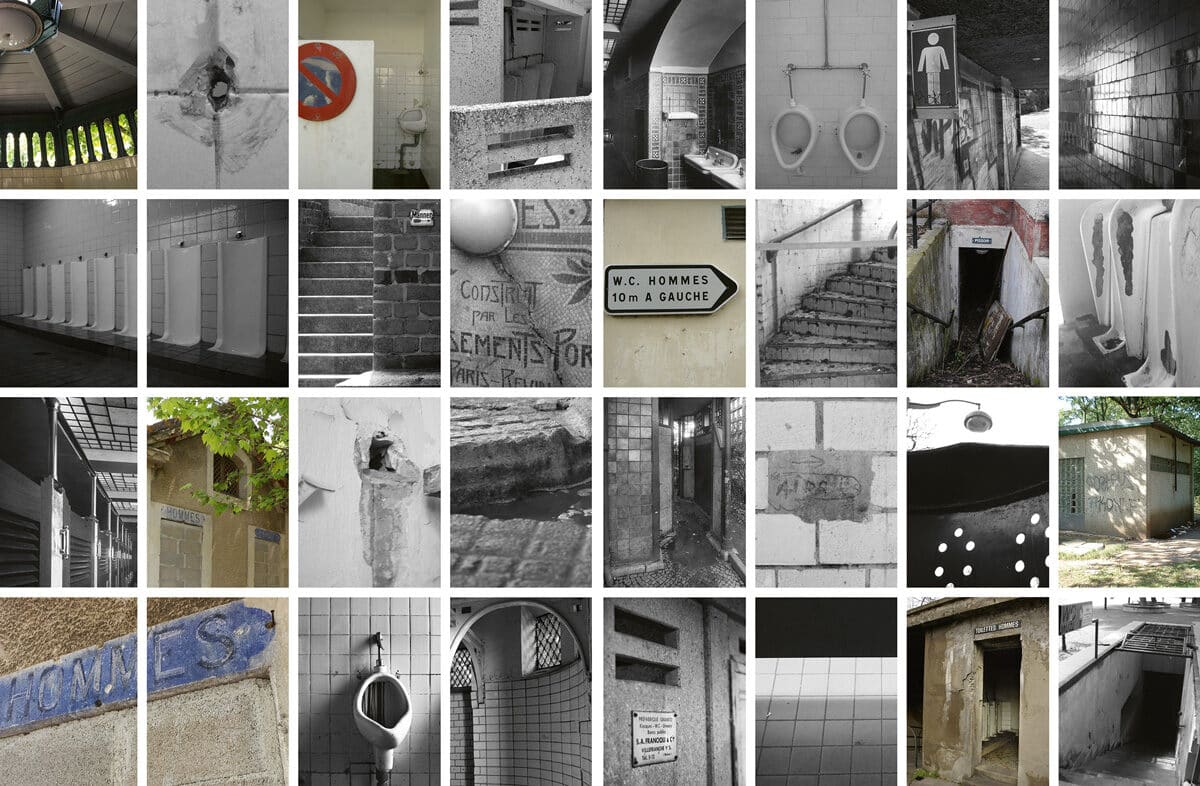

Les Tasses makes your own photos interact with period images. Why?

Les Tasses

invites contemporary art to dialogue with the past. By assembling these old photographs, I tried to build a bridge between narration and memory. I’ve been collecting them at flea markets, online or at yard sales, for the past ten years or so. None of them are sourced or dated. Their authors and the people depicted are unknown. Different in their textures, sizes, origins and times, they provide implicit clues and draw a clandestine territory in the public space. Anonymous – the title I have given to this chapter – thus reads like a quest for origins.

Anonyme / Les Tasses par Marc Martin

The series presented in this book all have specific aesthetics, why did you emphasise their differences?

I wanted to give back to these libertarian places – which have sheltered so many shivers – their disturbing part of sensuality. These atypical places of passage saw the social classes fade, the different cultures mix… High and low culture rubbed shoulders there. The walls reduced the borders and enlarged the space. If one crosses the universe of Proust, Genet, Fassbinder or Chéreau in my photographs, it is not by chance. They too were inspired by the pissoir. All in all, these places that are said to be creepy were not a dead end.

My series Strangers in the Night, for example, explores them at nightfall. Thanks to a deliberately discreet device, between erotic documentary and ethnological reportage, I captured the nightlife of these semi-private public places. I liked photographing it at dusk. Thus, the censorship disperses and dissolves in the decor.

You also chose to give a voice to many people – historians, sociologists, elders… What did they bring you?

Gathering testimonies of elders was the foundation that supported the project. Their words nourished my imagination. It helped me reflect on the unstable balance of our singular lives, our irregular itineraries. Emotions come through images and others through words, through lived experience. Then, historians and sociologists have analysed my approach. Their words, inspired by my photographs, has sometimes revealed them.

This book is paired with an exhibition, how did you imagine it?

I see the exhibition as an extension of the book. Since its opening at the Schwules Museum in Berlin in 2017, it has come a long way. If the stops in Munich and New York have recently been postponed, the one in Brussels has been captured in 3D. The virtual visit to LaVallée takes us, for example, to a former industrial building transformed into an alternative contemporary art centre. The first room treats the historical part with archive documents and the other rooms expose my artistic vision. An event is also planned in Paris. Given the new sanitary conditions, the exhibition will be held as soon as possible. Information will be available on my website!

Les Tasses, Toilettes publiques, Affaires privées, Agua editions, 58€, 300 p.

Anonyme / Les Tasses par Marc Martin

Anonyme / Les Tasses par Marc Martin

© Marc Martin