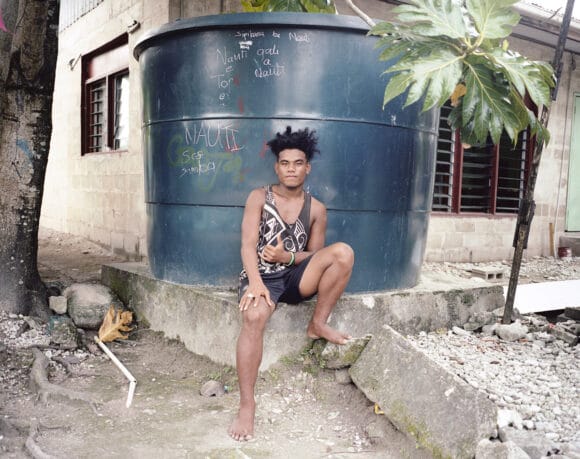

During a one-month stay in Tuvalu – an archipelago lost in the middle of the Pacific Ocean – Julia de Cooker carried out Funafuti, a project dedicated to this territory, condemned to sink into the surrounding water, and to its inhabitants, buried under the shadow of globalisation.

“How do we inhabit the world? This has been the question that has carried me for many years on my peregrinations, whether they take me to the arctic lands of Svalbard, or to the tiny islands of the Pacific. How did we get there and why do we stay there?”

Julia de Cooker asks herself. After documenting the daily life of the inhabitants of the world’s northernmost city, the Franco-Dutch photographer travelled to Tuvalu, an archipelago doomed to disappear one day because of global warming.

A microscopic territory, lost in the vastness of the ocean, populated by resilient inhabitants who persist in existing, in a hostile environment – or in the process of becoming so. “In Tuvalu, there is no question of tourism, it is the second least visited country in the world – only a few hundred foreigners a year”, adds the photographer, who spent a month in the country to carry out her project. An immersion in a restricted space, dominated by water, acting both as a reassuring landmark and a sinister agent, condemning them to drown, and cutting them off from the rest of the globe.

Losing one’s authenticity

Tuvalu is about fifteen kilometres long and between fifty and four hundred metres wide. On this narrow piece of land, stretched from north to south, all corners are quickly explored and the days start to blend together. “But it is only when you feel like you have been around it 20 times that you really start to discover the island”, says Julia de Cooker. A recurrence that can be found in her images. Everywhere, vegetation and white sand blend, evoking the illusion of a lost paradise. The treatment of colours – contrasting, as if the waves had erased the overly bright tones – completes the uniformity of the whole.

However, here and there, details break the routine and convey a certain surrealism. “The country, a former English colony, is not spared by globalisation, which is gradually nibbling away at its culture. The importing of Asian products takes precedence over local gastronomy and access to social networks influences daily life. Because Tuvalu is no longer isolated, the archipelago is afraid of losing its authenticity, its identity”, explains the photographer. Another contradiction is that environmental issues are dealt with through “major seminars”, and the island is witnessing the emergence of reinforced concrete infrastructures designed to protect the inhabitants from the inevitable. Some unusual, senseless constructions, breaking the utopian image of a territory bathed by a hot sun and licked by turquoise water. “Tuvalu puts us – Westerners – in front of our own contradictions”, the artist comments.

A relationship of domination

It is this ambivalence between one’s own identity and the destructive power of Western culture, between the inevitable end of a country and its desire to endure, that Julia de Cooker wishes to study. By immersing herself in the culture of the archipelago, the photographer discovers amusing singularities. “Miss Tuvalu, for example, does not meet the selection criteria of a Miss Universe: they have their own canons of beauty and remain faithful to them”, she notes. More than a documentary study of a community’s ecological and societal issues, the artist turns Funafuti into a philosophical series. “Nowadays, we no longer live in the world as we should, and that’s a problem. We have cut ourselves off from the rest of the living world and a certain standard has gradually been imposed all over the world. Comfort is becoming global and seems to be smoothing out the original diversity of habitats”, she states.

On site, as close as possible to the people, she observes and thus deconstructs our relationship with others. Should cultures be classified? Why are the customs of certain peoples being erased, passed under the steamroller of a “westernized world”? Could another way of life also slow down climate change? By discovering the images of Julia de Cooker, the viewer is confronted with their own shortcomings, and gets to know an unknown island. An ecosystem set aside because it is too small to arouse interest. A relationship of domination that the artist wholeheartedly denounces here. “Humans put their own land at risk because of the relationship they establish with it, which could be quite different, just like the traditional ways of life that still exist – but for how long?” she wonders.

© Julia de Cooker