Matthieu Chazal, a traveller, poet and photographer, created his Chronicles in Iran. A collection of black and white wanderings captured on film, freezing his impressions of a territory as beautiful as it is mysterious. At the heart of this intriguing country, he explores and tackles various themes, notably the gendered segregation of public space. A solitary journey, which takes us away from the routine of everyday life. Interview.

Fisheye: How would you introduce yourself?

Matthieu Chazal: I’m a photographer and a traveller. So, with the pandemic, I became a photographer in “slow motion”, like many others.

Why did you turn to photography?

I started photography late, when I was in my thirties. What brought me to it was, above all, the desire to go out and see the world. I first worked as a journalist for a few years, for the daily newspaper Sud Ouest, in my native region. I left it, and the valleys of Aquitaine to produce “major reports”, as they say, particularly in West Africa. At the time, I had taken a video camera with me, which I quickly exchanged for a still camera. This light, discreet, easy-to-use tool became my travelling companion.

What do you like to capture?

My approach is both documentary and personal. I try to develop images that suggest more than they inform, that are more evocative than descriptive. I don’t cover a subject per se or focus on specific characters. Rather, I explore territories with multiple roots, from the Balkans to the Middle East. I meet the various communities that live there and address different themes – identity, memory, migration – that shake and have shaken this region of the world, from ancient times onwards.

You have graduated in geography, philosophy and journalism. How have your studies influenced the way you work?

Geography is a traveller’s first encounter with a territory and its landscapes. It shapes the lifestyles and temperament of those who live there: the people of the coast are not those of the desert, those of the plateau are not those of the valley… Geography immediately brings history into play: In Iran, Persepolis, the capital of the Persian Empire conquered by Alexander the Great, is a good illustration of these places of confluence, of exchanges as much as of cultural struggles.

Philosophy nourishes the reflections around these themes, often bringing out more questions than answers. Journalism comes into play when current events invite themselves into my travels, or when I go to confront them – as in the Balkans with the migratory crisis, or in Iraq and Syria, with the fight against the Islamic State. There, journalism provides the keys to try to decipher the ongoing story.

How did the series Chronicles of Iran come about? What got you interested in this country?

Iran borders on Turkey, which is a country I know very well. When you travel as far as Mount Ararat, in the eastern reaches of Anatolia, Iran is there, near, closed, mysterious, and therefore extremely desirable. This country conveys a lot of fantasies, and a bit of fear: you tiptoe there, as the authorities are rather suspicious of Western travellers with cameras. It is a dive into the unknown, within a large country – almost three times the size of France! – with a mosaic of landscapes and peoples: Turkmen, Azeris, Arab Kurds…

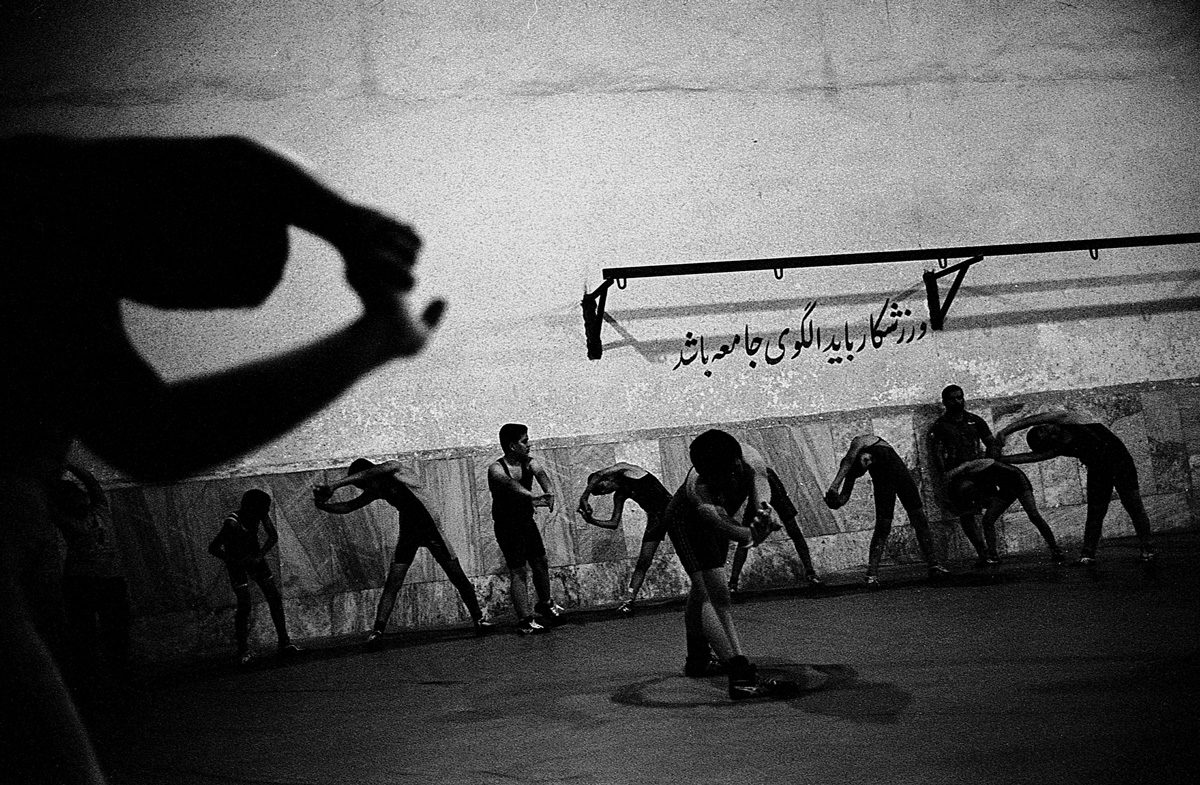

In different cities of the country, I attended the religious celebration of Ashura, the rituals and processions that take place during the month of Mouharram… As I made these discoveries, these Chronicles took shape, focusing on religious fever, separation based on gender and the pressure exerted by the mullahs’ regime in the public space.

You have documented the gendered division of public space in this series. Why this particular subject?

The subject was self-evident. The gender division in public space becomes obvious as soon as you take your first steps in the country. First of all, in public transport, there are spaces strictly dedicated to both genders. And then there are few places where women and men can meet, cafés are rare and supervised, few opportunities for bodies to get closer, few lovers on public benches… On the beaches of the Caspian or the Persian Gulf, the contrast is striking: men bathe and bask in the sun while women timidly go into the water, fully dressed…

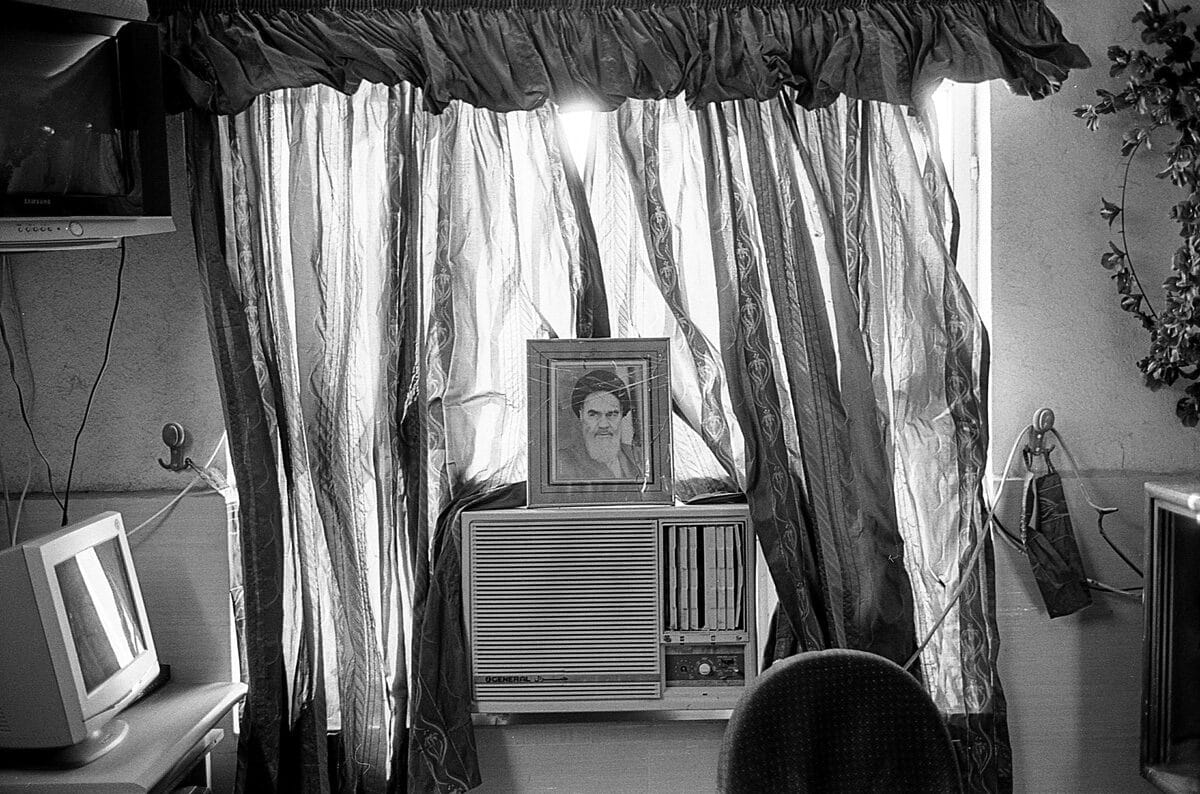

During religious celebrations such as Ashura, the faithful men stand on one side, the faithful women on another, under the watchful eye of the Guardians of the Revolution. Women only drop the veil in private, at home, behind the curtains that are always drawn. But as soon as they have to leave the house, they nervously arrange their outfit, which must not emphasise their shape, and constantly readjust their veil.

What other themes have you explored?

This series is about the separation of the body. It echoes one of the major themes that I explore in my Chronicles: that of the border. The border as a threshold, open or closed – a bridge that connects or a wall that separates.

What did you learn from your travels there?

I have been to Iran five times, often on month-long trips, which is as long as my visa allowed me to stay. I remember the beauty of the country and the great hospitality of its people. But there is also the authoritarian regime that weighs on the whole society. Almost all Iranians would like to change the regime, but through reforms, rather than a revolution. Because the repression is violent, intractable. The Guardians of the Revolution are everywhere, they create a scary climate. On top of that, the economic embargo smothers the inhabitants in their daily lives. So, there is a kind of renunciation, and those who can leave do, eventually.

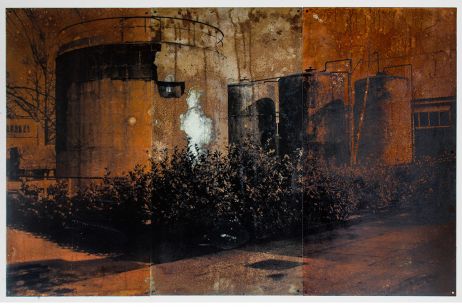

Why did you choose to photograph in black and white? And film?

This was a conscious choice. Black and white and film give the images a timeless quality. I tried to tell the story as a tale rather than a reportage.

What artworks inspire you when you travel?

When I develop a photographic narrative, the works of writers and poets inspire me. Like Nicolas Bouvier, who recounts his journey from Yugoslavia to Afghanistan in L’Usage du monde. The book was written some ten years after the journey, and the notes taken during his peregrinations are mixed with memories and imagination… I”m also thinking of Herodotus, who puts otherness at the heart of his Investigations, because when you travel from Athens to Persepolis, you sort of follow in his footsteps…

There is also cinema: Stanley Kubrick’s great films. I think of Barry Lyndon, with his meticulous compositions, as well as the long shots of Turkish director Nuri Bilge Ceylan.

And in photography?

I always think of travelling photographers: like Josef Koudelka and Robert Frank, Klavdij Sluban who navigated the Black Sea, Vanessa Winship who went to the Caucasus and the Balkans, but also the work of Jason Eskenazi, one of my fellow travellers.

“Chronicles” evoke the wanderings of a long-term project, how did you work on them?

I have been travelling back and forth between the two shores of the Bosphorus for several years now, on trips that last several months. I am quite mobile and often leave the big cities for villages and provincial towns. I experience both highs and lows – wandering, waiting. I’m lucky enough to be able to track down various opportunities along the way, ordinary scenes taken on the spot. The poetry of everyday life punctuated by pagan or religious celebrations, commemorations, weddings or funerals… All these events that bring people together trace my itinerary and give it its rhythm.

How will this project end?

I am working on the publication of a book that will bring together photos from these Chronicles of Iran, the Middle East, the Balkans and the Caucasus. There are still some pieces missing from the puzzle that I plan to bring back soon. Above all, I hope to get back into motion after so much immobility, due to the pandemic.

© Matthieu Chazal