The 38 year-old Swiss photographer Virginie Rebetez is fascinated by those missing, those absent. Through her work, she takes on the role of a detective, investigating the themes of loneliness, sadness and mourning. Her series Out of the Blue follows the story of Suzanne Gloria Lyall, an American student who has been missing for almost 20 years.

Fisheye: What do you like in photography?

Virginie Rebetez : The fact that the photographer is both outside and inside the scenes he is capturing, like an observer but also like a witness. He has to be present yet invisible at the same time. When I started, I really liked war photography and photojournalism, but then I discovered that I could engage with my pictures, and tell a story in a different way.

How would you describe your photography?

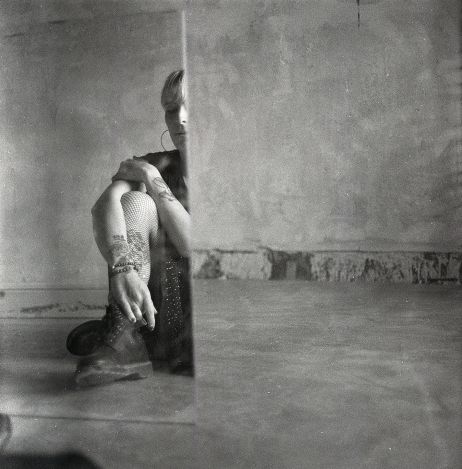

My work could be defined as both documentary and conceptual. I focus on themes like absence, death and memory. I like to transform the ‘invisible space ‘ generated by absence, to create something visible, tangible to help deal with loss. Through my personal implication in the images- either physically or through other interventions – I use photography as a medium to question our relationship with death.

What gave you the urge to do a series on a missing person?

I really started to think about this subject when my great aunt, who was terminally ill, asked me to take her last portrait. This event acted as a turning point, and I became interested in the invisible, in traces left after death or an absence, in the impact of unresolved stories. I am fascinated by our need to feel some sort of closure. For some years now, I have been checking different American websites dedicated to missing and unidentitfied persons. There, I read the people’s descriptions, their physical characteristics, and look at the images that represent them. It is truly touching.

How did you find Suzanne’s family?

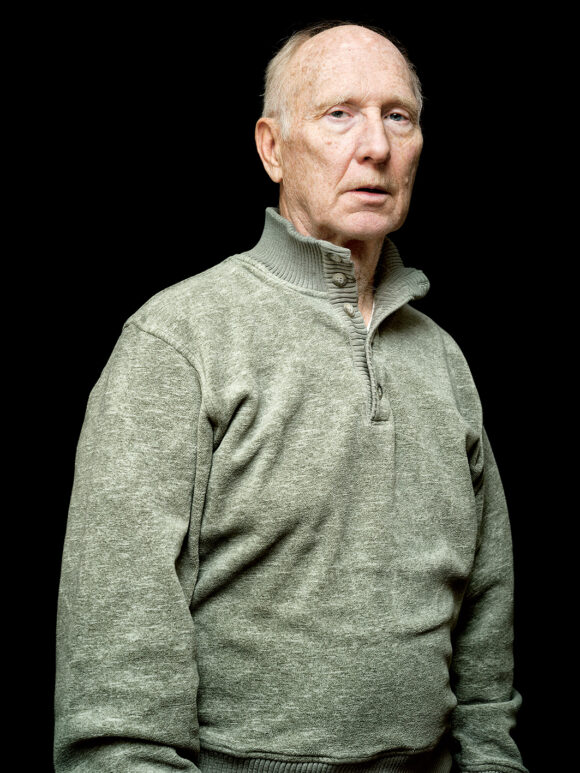

I started working on this topic when I was in New York. I had already started doing research on the Internet to find a family that would live in the State. I quickly found the story of Suzanne Lyall through her parents’ organisation for providing assistance to others affected by loss, ‘The Center for Hope’. I met them soon after. For two years, we shared a lot, talking, exchanging stories and adventures… Those were very special moments, that helped build trust and respect.

How did the family react to your project?

They were truly touched by my project. It was also important for me to keep them updated, and tell them everything about the development of the book. They loved it, and were happy that Suzanne’s story was spread in the art world. When the book was released in New York, we even invited Mary, Suzanne’s mother to be by our side. It was an important moment, for us both.

Was it difficult photographing this type of story?

In all my projects, I deal with personal and sensitive stories, so it is very important to know where the limit is, what is right and what is inappropriate. During the process, I asked myself many times if I was respectful enough, if I had the right to do it. But over the years, I have learnt to trust my instincts. I have tested many things, and I have always known immediately when I had crossed the bounderies. You just have to find your balance.

Why did you decide to publish a book?

I have always known it had to be a book. Because of the ongoing investigation, and the very nature of the subject, I had to use various materials coming from different sources. It was important for me that Suzanne’s story traveled around the world. I wanted it to be seen by different kinds of people, so a book was the obvious choice.

How did the book come together?

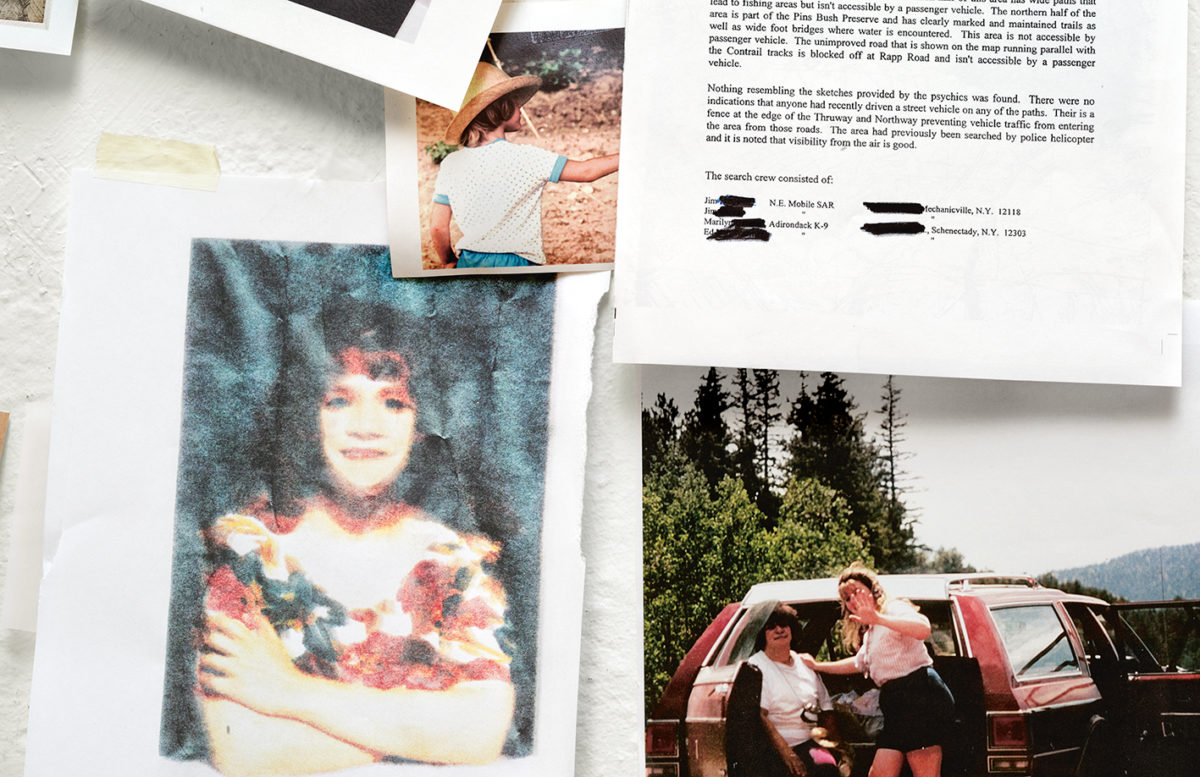

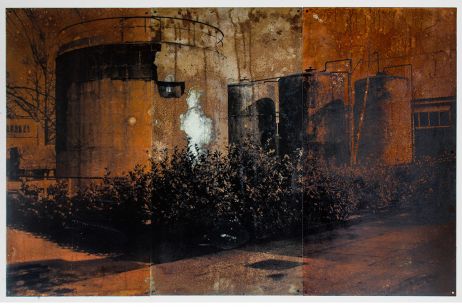

During my stay in New York, I met Suzanne’s parents several times, and even got to photograph many landscapes around the place she disappeared. I then came back to Switzerland and started arranging those images, starting to create what I wanted to say. After that, my publisher and I starting working on the project together. The main difficulty was finding a relevant way to combine all the different materials – the family pictures, the Police images, the 19 year correspondance with psychics, and my own material. For two years, my studio wall was covered with hundreds of pictures. We decided to include it in the book by re-photographing some parts of it. These new images, composed with images from different sources, create a narrative rhythm in the book.They acquire their own new status and represent my own voice in the story, among the ones of the family, the police and the psychics. It is also a reminder of typical ‘police investigation wall’.

How did you feel during this whole process?

For two years, I developed a relationship with Suzanne’s parents. I think the fact that she was only one year older than me helped me create something meaningful with them. It felt like Suzanne was besides my at all times, I was often speaking to her in my dreams’.

© Virginie Rebetez