Michael Dillow is an American photographer and a Master of Fine Arts candidate. His series Getting Better is a touching and intimate portrayal of the struggle against the illness that is addiction. An experience inside treatment facilities that changed South Florida’s landscape, coined ‘the international recovery capital of the world’.

Fisheye: Where did your passion for photography come from?

Michael Dillow: Growing up in the middle of Philadelphia’s skateboard scene, I first began making photographs and videos of my friends and myself skateboarding. We were enamored with how things appeared frozen in a photograph, This is where I first recognized the medium of photography’s power to provide evidence, to make a historical record. At first, my photographs simply provided proof of the tricks we had accomplished. It wasn’t until later when I began to point my camera towards the culture that surrounded me, that I recognized the power and agency that a photograph can hold.

How did this help define your style?

Since studying at Temple University, I have been attracted to a documentary approach. In thinking and working in this genre, I have developed an acute awareness of what surrounds me and an insatiable desire to try and better understand it. There are endless amount of narratives playing in a community. The camera grants me the ability to try and capture them— to look beyond the surface, and to provide an honest and intimate view into the communities that I am both surrounded by and a part of.

What is the story behind Getting Better?

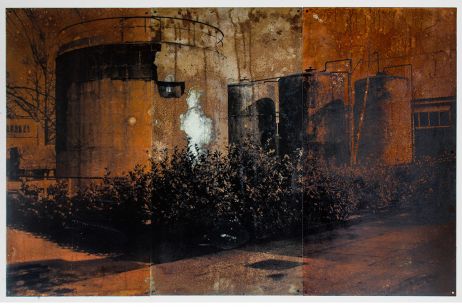

In 2015 alone, there were more than 52,000 drug overdoses resulting in death, and that number continues to skyrocket. It can be felt and observed across all age groups, all races, all classes of citizens, and in all areas of the country. South Florida is coined, “the International Recovery Capital of the World,” where there are more drug and alcohol treatment facilities in 100 miles than in the rest of the country combined. There is little to no regulation and, more importantly, no oversight for care given to those who seek it. It is nearly impossible to recognise the legitimate from the illegitimate businesses, they all seemingly offer an identical solution.

Why did you choose to document this?

Years before I decided to do this series, I experienced this industry firsthand. Through my own personal experience, I was able to gain an insider perspective. It allowed me to see past the sobering statistics and palatable media coverage of this epidemic. I wanted to provide an intimate portrait of both those in an early stage of recovery, and of the ways in which this industry has impacted South Florida’s landscape. My hope is that this work will combat the stigma and stereotypes that surround the disease of addiction and initiate a dialogue where it is universally recognized as a medical condition, as opposed to a momentary lapse of judgment or sign of weakness.

How long did you spend shooting there?

I have been both researching and shooting for this project for the better part of a year and a half.

How did you meet your models?

At first, I was attracted in capturing evidence of the recovery industries presence on the surrounding landscape. But due to the vast quantity of recovering people there, I would regularly encounter subjects while out shooting. Through conversation about both my own experience, and about what I was doing, I would eventually ask permission to make portraits of the people I encountered. As the series progressed, and my intentions behind this work became known amongst the recovery community, I was granted access into a number of halfway houses (or sober residences). I started to spend large quantities of time in these residences, where the occupants and I would swap stories about our shared experiences. It was important for me to make this work a collaboration between them and myself.

What did you learn through this series?

I already knew about both, the disease of addiction, and of the industry of recovery. However, after sustained shooting in the same homes for long periods of time, I became acutely aware, and reminded, of the power that the disease of addiction holds. The people residing in these homes changed on a weekly basis—some decided to go back out and use, despite their earnest effort and strong desire to change. Not everyone is as lucky as I am. It was a difficult task to make such personal work amidst an epidemic that, in one way or another, will always be present—people will continue to die.

What is your favorite photo?

This is an impossible question to answer. I have about 5 images that, in my eyes, are the foundations for this series. One of them is the portrait of the female subject holding onto the back of her boyfriend. For me, this image highlights the vulnerability that those in early recovery experience and the desire to establish meaningful connections with people. It’s rather poetic—as if the two subjects are blending together as one.

© Michael Dillow